THIS has been an easy blog to write, and an even easier one to illustrate. Anyone with a modern camera can take pictures of today’s Venice, and its famous canals and gondolas, that look like the work of the painter known as Canaletto.

Strategically located on a cluster of harbour islands at the head of the Adriatic Sea, and immensely wealthy at one time from trade and skilled crafts such as the glass-workers of Murano, Venice was always on the itinerary of the old-time traveller and artist.

Venice was founded by refugees from the fall of the Western Roman Empire, who came to live on the islands to be safe from marauding barbarians. The islanders soon found that their new home was a good base for trade.

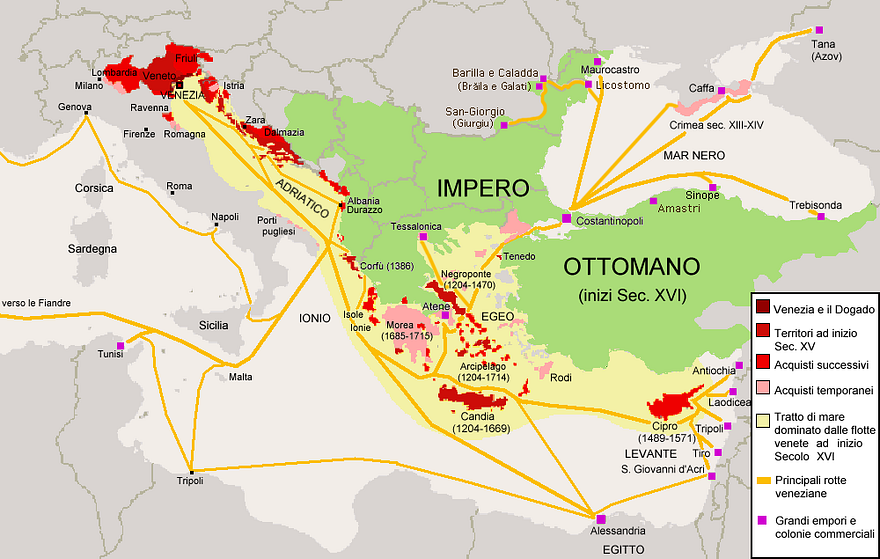

By the time of the Renaissance, the Venetians had established a surprisingly far-flung empire of their own, ruling over territories as distant as Cyprus. The long-distance traveller Marco Polo was a Venetian of this era, too.

Precariously located along the edge of an expanding Ottoman Empire, the Venetian Empire — well, not officially an empire; it was always called La Serenissima, the Most Serene Republic — gradually shrank, thereafter, until the Venetians were bottled up in their home waters once more.

The Most Serene Republic was ruled by an official called the Doge, the local dialect equivalent of Duke, Dux or Duce.

The Venetians established once of the first modern factories, the Arsenale or Arsenal, which produced one war-galley or trading-ship every day by means of assembly-line techniques. The Arsenale still stands: it looks like it was built in 1900, not in the 1300s (when the greater part of it was constructed).

The Venetians were able to hang onto their maritime empire for as long as the Turks remained landlubbers. However, once the Turks got a navy of their own, it was all over for the more distant Venetian colonies.

The Most Serene Republic was finally abolished by Napoleon, who was good at abolishing things. He also abolished the Holy Roman Empire, another old empire ruled (rather loosely) from Vienna; not to mention miles, feet and inches over the greater part of Europe.

Napoleon made himself King of Italy, meaning a chunk of the north that included Venice, and his brother Joseph, King of Naples and Sicily. After the Bonapartes were booted out — the geography of Italy inspiring many a cartoonist on the subject — Venice was taken over by a an HRE which had bounced back under the new title of the Austrian Empire.

For a time, Austria would rule much of Northern Italy. However, at the beginning of the 1860s, Venice was liberated from the Austrians by the unifiers of Italy, who proclaimed that the city was free once more — and would therefore now be ruled from Rome, not Vienna.

Venice also has a sizeable Jewish community, with five historic synagogues, all of them built in the 1500s CE, that catered to different congregations: the ‘German’, the ‘Spanish’, the ‘Levantine’, the ‘Canton’ and the ‘Italian’. Commemorative plaques and a sculpture encourage passers-by to remember the Nazi holocaust. Some of the Jewish community of Venice were tracked down and deported to concentration camps, but, luckily, thanks at least in part to the heroic refusal of one community leader who committed suicide rather than be forced to name names, the majority were not.

These days, Venice is perennially sinking into the mud and has a general air of having seen better days about two hundred and fifty years ago, after which it lost its independence and was bypassed by modern land transport and the Industrial Revolution.

Of course, that only makes Venice more touristy. Where else can you walk the streets of an eighteenth-century city which is still just as it was?

In my book A Maverick Pilgrim Way, from which the map of Italy at the start of this post is adapted, I describe how I’ve been to Venice before.

Before returning once again in October 2017, I’d read about a rise of anti-tourism sentiment among its dwindling population of 55 thousand, due to the general strain caused by 22 million visitors a year, excessively high prices for everything as a result, and, even, air pollution from cruise ships.

The last of these is a surprisingly serious problem. Several of my photos in this blog show hazy air. Ships’ engines do not have emission controls or limits on sulphur in the fuel and are still allowed to pump out black smoke all day long. The theory is that it all blows away at sea and anyway, there is no government to regulate it.

Well, that’s as may be, except when they get to Venice, where it is bad for health and also eats away at old buildings and statues. Anyhow, here are some more attractive pictures!

This time, to escape the overcrowding in summer, I decided to come in October. I stayed in the Rialto district at an Airbnb for 40 Euros or the equivalent of US $50 a night.

(It’s a sign of Venice’s popularity with the tourists that every other city also seems to have a cinema or a swimming pool called the Rialto, or the Lido, another district of Venice.)

I got a seven-day pass for the water taxis, which are called vaporetti, or vaporetto in the singular. This cost me 65 Euros or about US $ 77. Vaporetto basically means ‘little steamer’; that is, as opposed to the poles of the traditional gondoliers.

A 40 Euro museum pass got me into the Doge’s palace, into a number of Venice’s splendid museums and galleries, and most of the historic churches.

I had to get a separate pass for St Mark’s Basilica and the bell tower in the Piazza San Marco, bypassing the queues for a physical ticket. Gong up the bell tower and looking down on Venice is a must! I’ve shown some of the photos I got from here, already, and here is a video as well.

I went for a ride on a gondola, costing 80 Euros for fifteen minutes, which I split with an American woman. The gondolier told me that even he couldn’t afford to live in Venice these days.

And I went to famous Venice Biennale art show, which had a New Zealand exhibition by Lisa Reihana, all about the colonisation of the Pacific, set up inside the factory-halls of the Arsenale. The 2017 Biennale is the 57th; the Biennale has been going since 1895.

The Russian exhibition, Theatrum Orbis, was taken up with several thought-provoking themes that included online immortality and the surveillance society, while the American exhibition, by the artist Mark Bradford, was also impressive if a little gloomy.

I also went to see a play called Fuorissimo, meaning ‘crazy’, in which the characters all wore symbolic masks. This is an old tradition called Commedia dell’Arte, a stylised form of satirical entertainment based on stock characters identified by their masks, as in some Asian countries. In the local context, it probably descends from Greek and Roman drama or Mediaeval morality plays.

The meaning of Commedia seems to lean more toward more worthy themes than the word ‘comedy’ usually does in English. Maybe this reflects the influence of Dante’s Divine Comedy, at the heart of which is the Inferno. So, we aren’t talking about Mrs Brown’s Boys, in other words.

That reminds me, also: the Venetian dialect, which is distinctive, gives us the word ‘zany’ as well as Doge. Zany comes from the local pronunciation of the name of one of the stock Commedia dell’Arte characters, a fool called Gianni, or John.

Here are some photos of artwork that wasn’t part of the Biennale, just interesting modern street art, to show that not everything in Venice is ancient.

And though it might be because of all the air pollution, I have to say that I’ve rarely seen sunsets like the ones I shot in Venice!

On Sunday 22 October 2017, the regions of Veneto (where Venice lies) and Lombardy voted for greater autonomy from the Italian state in regional referendums. Perhaps La Serenissima is being restored to some degree!

But before that, after I left Venice, I headed on south and hooked up with the Via Francigena pilgrim trail near Pisa. I am going to write about that in another post!

Here is my Amazon author page. I’m also publishing my books, progressively, on other platforms.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!