ONE of the blog posts I’m most proud of on this website is called Dunedin and the Taieri Gorge Railway, published back in 2019. It’s partly about a trip taken by my friend Chris, who took the beautiful photos in that post, and my dad Brian, on the Dunedin Railways tourist train up the Taieri Gorge, inland from Dunedin.

This March, I decided to do the Taieri Gorge Railway for myself, and then to go to a concert by the band Six60, and then to visit a wildlife rescue centre called the OPERA, the Otago Peninsula Eco Restoration Alliance.

I’ll come back to the Six60 concert and the OPERA a bit further on in this blog.

But first, since it is what I did first, I’ll talk about the trip up to the Taieri Gorge, up which the Otago Central Railway used to run, from Wingatui Railway Station just outside Dunedin, by way of the low-lying Taieri Plains, and then up to the high plains of the Maniototo, all the way to Cromwell. It rose from the low plains to the high plains by way of the Taieri Gorge.

Looking down on the Taieri Plain, these ramparts used to be known as the ‘Garden Wall.’ Whence, the title of a local history I bought before going on the train, Over the Garden Wall: The Story of the Otago Central Railway, by Jim Dangerfield and George Emerson. It must be very popular, because there have been at least four successive editions.

These days, a Dunedin Railways tourist train runs up the Taieri Gorge as far as Pukerangi. Pre-Covid, it used to go to Middlemarch, 22 km further on into the Maniototo, which means ‘plains of blood’ in Māori. Fortunately, that’s just a reference to the red tussock of the high plains!

The higher reaches of the Otago Central Line, from Middlemarch to Cromwell, are now the Otago Rail Trail, for cyclists.

On the modern tourist train, you leave from the Dunedin Railway station, a sort of cathedral dedicated to the god of steam.

Complete with stained glass windows!

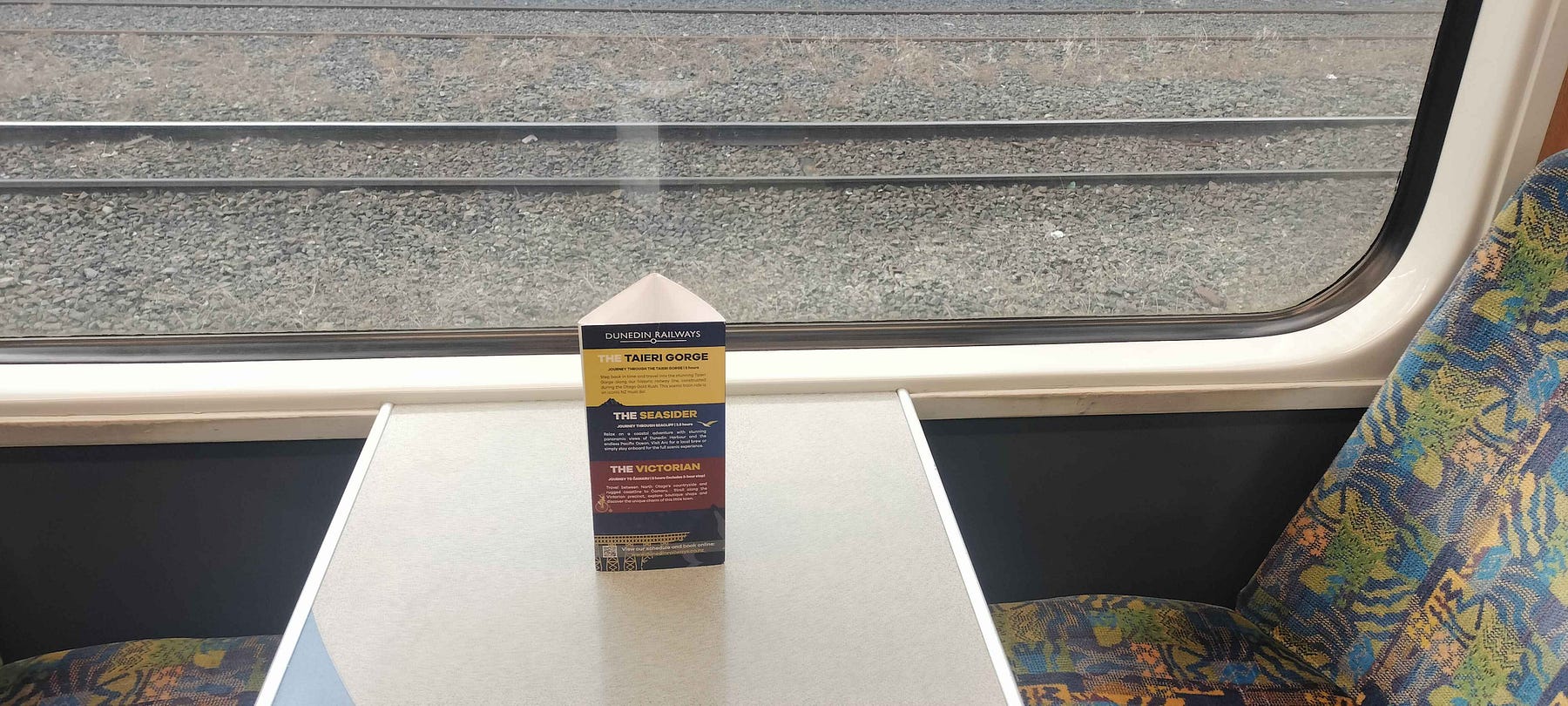

There are other excursions along the coast as well, the Seasider and the Victorian (to Oamaru and back), which none of us has done yet.

I did the Taieri Gorge trip on the 8th of March; here are some photos I took (you also need to see Chris’s ones in the old blog).

Here’s a video I made, of scenes filmed along the journey: the thumbnail is of the Taieri Plains.

Dunedin Railways also has an Instagram account, by the way: https://www.instagram.com/dunedinrailways.

That evening, I went to the Six60 concert that was being held on the Union Lawn, at Otago University. Six60 take their name from a big old house at 660 Castle Street in downtown Dunedin, which used to be a student flat where the band members lived, and which they now own.

Six60 use some of their profits to sponsor young musicians, who even get to play and tour with the band in some cases.

The next day, I went to OPERA on the Otago Peninsula, the long peninsula that runs from South Dunedin at its base, to Harrington Point at its tip. The OPERA is 22 km along the peninsula, which is also famous, among other things, for Larnach Castle, featured in another of my past blog posts about Dunedin, ‘Sounding Out Dunedin.’

Before you get to those more distant destinations, it is worth checking out South Dunedin’s historic city beaches, St Kilda — shades of Melbourne — and St Clair, which has a lovely esplanade.

There was a statue of a New Zealand sea lion, called Mum, the first to give birth on the New Zealand mainland in 100 years at Taieri Mouth, southwest of Dunedin, on New Year’s Day, 1993.

Traditionally, most New Zealand sea lions inhabited the coastal forests that used to be widespread in New Zealand, walking inland as far as two kilometres to find a suitable forest home. (Sea lions are more capable of walking on land than true seals, which they otherwise resemble.) They were known by several names in Māori, such as pakake and rāpoka, and hunting by Māori led their populations to decline.

However, the real death blow was dealt by the army of British and American whalers and sealers that descended on the country in the decades after Captain Cook.

Luckily, some populations managed to survive on the New Zealand Outlying Islands, most of which are partway or even halfway to Antarctica and, as such, considerably less attractive places to go a-hunting.

Apparently, all Otago sea lions are now descended from Mum.

From St Clair, I forged on to the OPERA, near the tip of the peninsula.

At the time of my visit (9 March) the OPERA was very busy looking after moulting penguins, such as the ones in the photo near the beginning of this post. Here are some others, that seem to be in somewhat better shape!

Once a year, in the autumn season of the Southern Hemisphere, penguins lose all their feathers and have to grow new ones, a process known as a catastrophic moult. During this time, they can’t go to sea to feed, and are thus at risk of starvation as well as dying from the cold.

To make things worse, the introduction of dogs, cats, and other mammalian predators to New Zealand makes the six species of penguins that live on the coast of New Zealand — a real penguin haven, second only to Antarctica — also vulnerable to predation during the moult.

Before the coming of mammalian predators, penguins moulting on the New Zealand shore only had local birds of prey (and the waddling sea lions) to worry about and could generally hide from them in the thick coastal scrub, which is precisely why New Zealand became such a penguin haven.

Unfortunately, the introduced mammalian predators of today can literally sniff them out and are more agile on land than the sea lions, or the penguins themselves. This is one of the two great problems for those who are trying to conserve our penguins, the other being changes in ocean food supplies as a result of global warming.

There’s more about this part of the country in one of my books, The Sensational South Island, on sale on my website a-maverick.com.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!