FROM Hatay, I travelled to Lebanon: a small but historic, Arabic-speaking country north of Israel, which has two interesting peculiarities.

The first is that Lebanon is less overwhelmingly Muslim than most Arab countries. About forty per cent of the population is Christian. Just under a quarter of the population practice the Maronite variety of Christianity, which is rather specific to Lebanon. This is an old form of Roman Catholicism, which acknowledges the Pope in Rome but permits priests to marry.

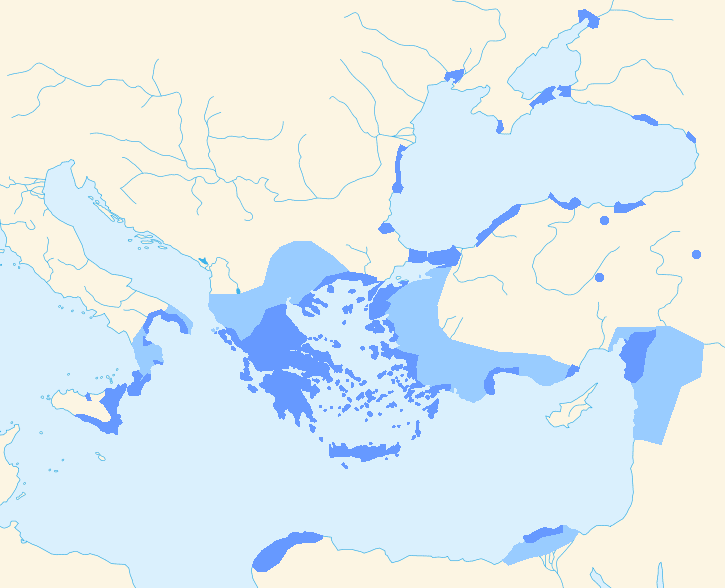

The Maronites get their name from the fact that their branch of the church was founded by Saint Maron of Antioch, the city now called Antakya in Turkey’s modern Hatay province, which was founded in the course of the colonial expansion of ancient Greece around the shores of the eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea in the last few centuries BCE.

The Maronites eventually migrated south to Lebanon and became Arabic-speaking. They conduct their liturgy in Syriac, an old language related to Arabic.

Lebanon’s Muslim community is also divided evenly between Sunni and Shia, and there is a Druze minority of about six per cent. The Druze practice a religion partway between Islam and Christendom. So, Lebanon is hugely diverse.

Lebanon became independent of France in 1943. There has been a convention since that date whereby the President is a Maronite Christian, the Prime Minister a Sunni Muslim, and the Speaker of the Parliament a Shia Muslim.

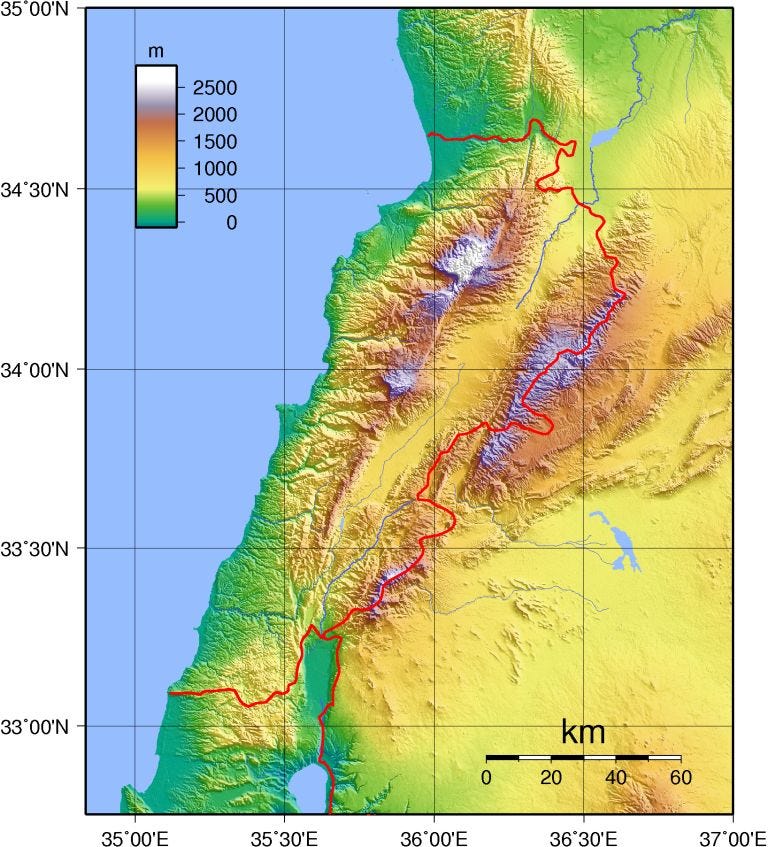

The second peculiarity of Lebanon is that it is mountainous and gets lots of snow. Most Middle Eastern countries are too hot and dry to get snow. Lebanon’s name comes from the Arabic phrase al-Libnan, which means ‘the White’, as in white as snow; and from similar-sounding phrases that mean the same in other Middle Eastern languages ancient and modern, including Hebrew.

On the slopes of Lebanon’s mountains, white in winter, the country’s famous cedars grow. The cedar appears very prominently on Lebanon’s flag.

I call Lebanon the ‘Ireland of the Middle East’, because it has been occupied for most of its existence by imperial powers. Although it is an ancient country, mentioned in the Bible, it has seldom been independent. Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Umayyads, Abbasids, Crusaders, Ottomans, French and Syrians have all ruled Lebanon.

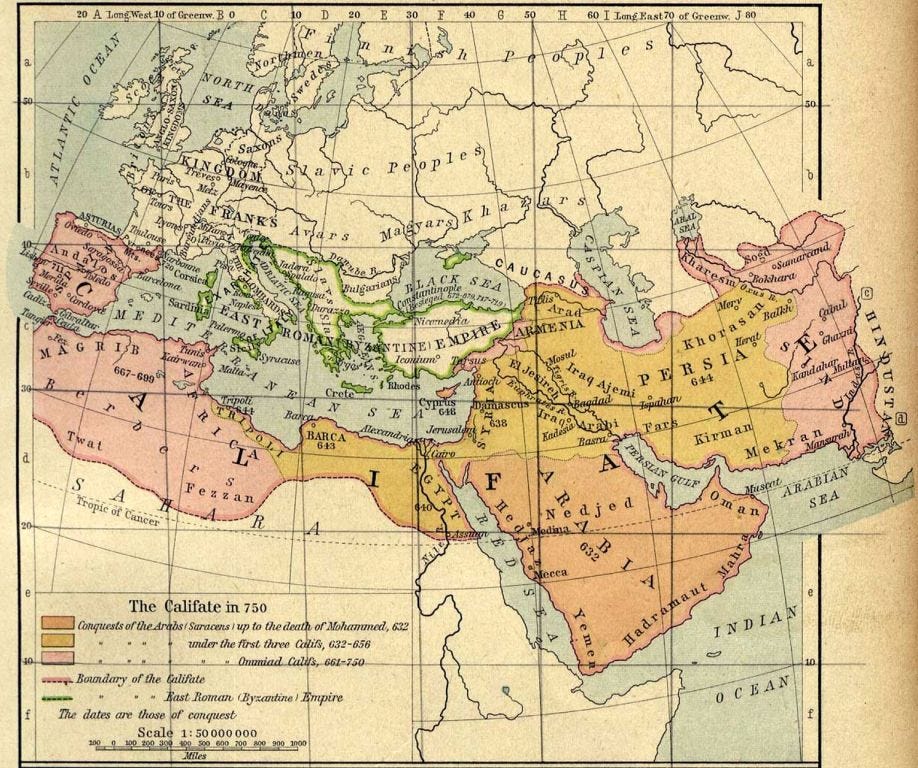

The Umayyads were early Muslim conquerors, rulers of a vast empire established soon after the death of Muhammad. The Umayyad Caliphate ruled over large Christian and Jewish populations in territories such as Spain, the Antioch region, Armenia and Lebanon, and was quite tolerant by the standards of its day; certainly, more so than Spain would be after it was reconquered by the Christians. Damascus was the main capital of the Empire, so Lebanon was quite close to its heart.

Like the Roman Empire before it, the vast and unwieldy Umayyad Caliphate soon split into western and eastern parts. This happened in 750 CE, eighteen years after the Umayyads were defeated in their attempt to conquer France.

The Caliph was, in theory, the ruler of all Muslims. In practice, and particularly so after the fall of the Umayyads, the office would normally be disputed. In later centuries, it also became purely ceremonial, much like the role of the British sovereign in the Commonwealth.

The Abbasids preferred to rule from Baghdad, rather than Damascus. Fabulous tales of the Caliph of Baghdad are set in the Abbasid era, which lasted from 750 CE to 1258 CE. During that period the culture of the Abbasids was much more advanced than that of Europe. And the eastern part of the Mediterranean world was vastly richer in material terms as well.

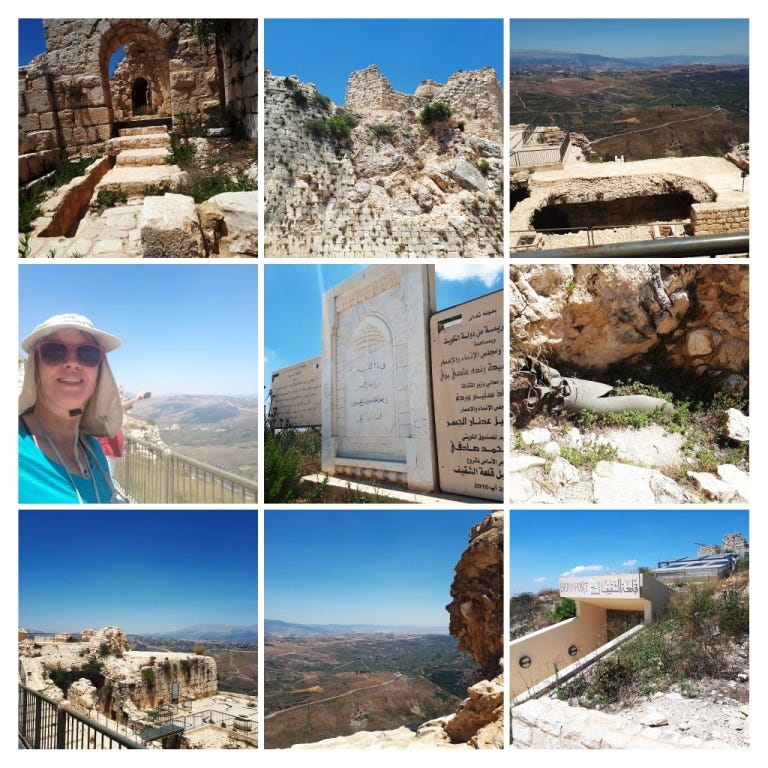

It was the Abbasids who did battle with the Crusaders: who established a foothold on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean for a while and built castles such as Krak des Chevaliers in Syria and Beaufort Castle in Lebanon, but ultimately failed to re-establish Christendom as the dominant force in this part of the world, just as the Umayyads had failed to conquer France.

The Abbasids made a distinction between their local Christian subjects and the Crusaders. The Crusaders were seen mainly as a sort of nuisance — people from poverty-stricken lands in the frozen north of the kind that had continually fallen upon the wealth of the Mediterranean from time to time; spiritual descendants not so much of Jesus, as of Alaric the Goth.

Wealthy Christian-majority cities in the eastern Mediterranean, such as Constantinople, were also pillaged by the Crusaders. The Christian rulers of Constantinople had to put fake gems in their crowns after the original crown jewels were carted off to Europe by their co-religionists. This reinforced the view that the Crusaders were in it for the loot.

It’s interesting to get a view of the Crusades from the other side!

Though the people of Lebanon were ancient and had spoken other languages in Biblical times, it was in the time of the Umayyads and Abbasids that they ended up speaking Arabic.

A second reason for calling Lebanon the Ireland of the Middle East is that it has a huge diaspora community. There are four million Lebanese in Lebanon but up to fourteen million, depending on how they are counted, overseas. It’s generally agreed that there are more people of Lebanese ancestry living in Brazil than in Lebanon!

A third reason is the country’s tremendous religious-community diversity, which is reflected in parliamentary and ministerial quotas, plus a tragic civil war from 1975 until 1990 in which the factions were organised mainly along religious-community lines. So, perhaps we could say that Lebanon is the Northern Ireland of the Middle East.

The Lebanese conflict was worse, though, with much of Beirut destroyed and 120,000 people killed, as opposed to only a bit over 3,000 in the Northern Irish (Ulster) Troubles that took place in roughly the same era. The amount of physical damage that was done in Northern Ireland was also pretty minor compared to Lebanon.

For all the ink that’s been spilled on the Ulster conflict — all the movies, all the marches and all the songs — it was a skirmish compared to the Lebanese Civil War, which was more like what is going on in Syria right now.

In terms of area, Lebanon really is small, as small as the Caliphates were huge. Lebanon’s total area is only a bit over ten thousand square kilometres, which is less than a twentieth the size of New Zealand and, indeed, less than Northern Ireland.

The country’s highest point is Mount Lebanon, 3088 metres high. There are two main mountain ranges, one inside the country and one along the Syrian border. Between the two lies the fertile Beqaa Valley, which contains the ancient ruined city of Baalbek or Heliopolis, and ruins of the Umayyad city of Anjar.

Although the Abbasid Caliphate was more advanced and wealthier than Europe, the Caliphate was effectively destroyed by the Mongol invasions, which the knights of Europe managed to fight off. Actually, the rugged terrain of Europe helped with the defence. The flat country of Iraq is easily invaded and over-run, as we have seen in more recent times. Ultimately, moving the capital to Baghdad hadn’t been such a good idea after all.

Thereafter, the Caliphate re-established itself in Cairo, and finally in Constantinople. It was in these later times that the office, finally abolished in the 1920s by Kemal Atatürk, became more and more ceremonial.

More significant was the fact that the Muslim world lost its mojo after the Mongols pillaged Baghdad, inflicting more material and spiritual damage than the Crusaders had ever managed. Before long, starting with the Renaissance and the invention of movable type — Muslims continued to write in flowing hand — the West began to pull ahead of the Middle East.

My guide told me that the Maronites brought the Renaissance to Lebanon, a Renaissance that penetrated no further into the Middle East. I don’t know whether he was being chauvinistic, but there was probably a degree of truth in what he was saying.

As to the 1975–1990 Lebanese Civil War, this was really a spillover of the Israel-versus-Palestine conflict. People in Lebanon who had got along quite well suddenly felt they had to taken sides, because of the constant provocations from the south. These days, Lebanon is also home to a million Syrian refugees and also to the militia of Hezbollah, which has been surprisingly successful at beating off the Israelis and destroying their tanks whenever the Israelis have tried to invade in recent times. Lebanon’s mountainous terrain means that the country is a sort of Switzerland or Yugoslavia from the military point of view; hard country that favours the defence in David-and-Goliath struggles, that would otherwise be won handily by the Israelis.

There are currently about one and a half million Syrian refugees in Lebanon, and about a quarter of a million Palestinian refugees. Poor Lebanon is bursting at the seams!

The country has seen worse tragedies, however. Before it gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War One, it suffered a terrible famine from 1915 until 1918 in which half the population at that time is thought to have perished. A combination of wartime blockade and mismanagement, and a plague of locusts, caused the famine. There are no monuments to the famine, perhaps because nobody wants to remember it.

Being a Maverick Traveller I tend to book places only a week before I arrive! So, I booked The Grand Meshmosh Hotel right in downtown Beirut, on the Saint Nicolas Stairs, a public stairway with 125 steps.

The area was mostly Maronite. Beirut has many communal neighbourhoods including an Armenian quarter. Every corner has the Lebanese Army. The army searches vehicles as car bombings are a constant threat from all sources, including the Israelis when bent on assassination.

When I landed in Beirut I asked the reception desk at the airport if they had any tours. I was told to “go find a person.” So, I found Sabina, a woman from Sweden who had been working in Bulgaria. Sabina was depressed and leaving Lebanon; she was out of money. So, I said I would shout her for the day. I got a local sim card and we had lunch. We took a local taxi from the downtown Hamra bus station to the Cola transport centre and caught a van taxi to Sur Beach near Tyre, an ancient and modern city, about 75 km to the south.

I noticed that people dress in what they want, shorts, short skirts. The cities of Lebanon are like Europe; no dress code is required.

At Sur beach we met Sabina’s friend Reda, who was looking after his father. Parts of the beach are public, other parts are private. This seemed to enforce a wealth-based and communal Apartheid. You paid for the privilege to keep the poor people out who would be Sunni and ignorant, said Reda’s father.

You could almost see Israel from Tyre. But you could not mention that name even among the Christians, I noticed, and had to call it Palestine.

Lebanon has a wall along the border of the actual Palestinian territories and not many are allowed through; only the United Nations, for humanitarian reasons.

Having been told that I needed to “find a person,” I didn’t know that the Meshmosh Hotel actually ran daily tours!

I was staying in a dorm room, hoping I would meet some people but that did not happen, so I went online and found a tour company by the name of Nakhal & Cie., just a ten-minute walk from Meshmosh Hotel. I then found out later that I could have taken tours from Meshmosh Hotel itself.

I toured the former Green Line, the local equivalent of the Berlin Wall. During the Lebanese Civil War, the Green Line divided Muslim western Beirut from Christian east Beirut. It was called the Green Line because weeds grew up in the no-man’s-land (so there wasn’t actually a wall, just a no-man’s-land). During the conflict, Israel, Syria and the Palestine Liberation Organization all joined in. For a long time, Israel reinforced the Green Line with dug-in tanks.

I found that many young people from all over the world were drawn to Beirut, doing internships of one sort or another for the United Nations. I met a guy writing policy to change the government’s views about refugees. At the Meshmosh Hotel I also met the parents of some of these young people, like a guy teaching English at an Armenian School and an English girl working for a Gay Rights organisation (the Lebanese government had just made homosexuality legal).

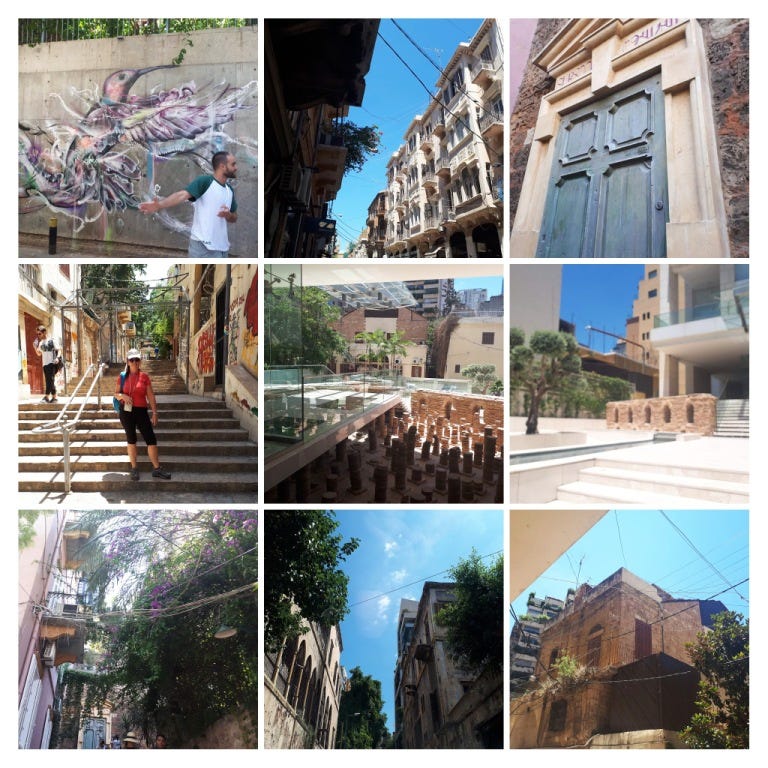

On my first day I went for a walking tour that I didn’t finish. This was called the Alternative Walking Tour of Beirut, which started at the top of St Nicolas Stairs on Wednesdays and Sundays. It was full of grumpy European men who were used to meek and mild woman.

Another tour, I was told, was Walk Beirut. This was led by the son of Mohamad Chatah, a Sunni economist and politician who was assassinated by a car bomb in 2013.

An organisation called Solidere, started by the former president Rafiq Hariri (assassinated by a car bomb in 2005), was redeveloping and reclaiming the waterfront area

A lot of buildings are empty as they are sold to Lebanese overseas, and the process of redevelopment is said to have gang and mafia connections. It is driving up real estate prices to very expensive levels. Many landlords are still getting pre-Civil War rents, so they let the buildings rot and then have them demolished. There is a movement to save the old buildings; apparently all rents are going to be very high next year.

I saw some old ruins that just had labourers working on them, not archaeologists; they were soon to be built over.

Hamra is the shopping area

Went for a walk around the waterfront on a Sunday. There were men swimming in water than was full of plastic. It wasn’t the best beach. Ramilah, where you pay, is better.

I visited the Maronite cathedral of St George, and Greek Orthodox and Armenian churches as well.

I toured one of the mosques and they gave me what I call a ninja suit to cover myself with. Loved the diversity.

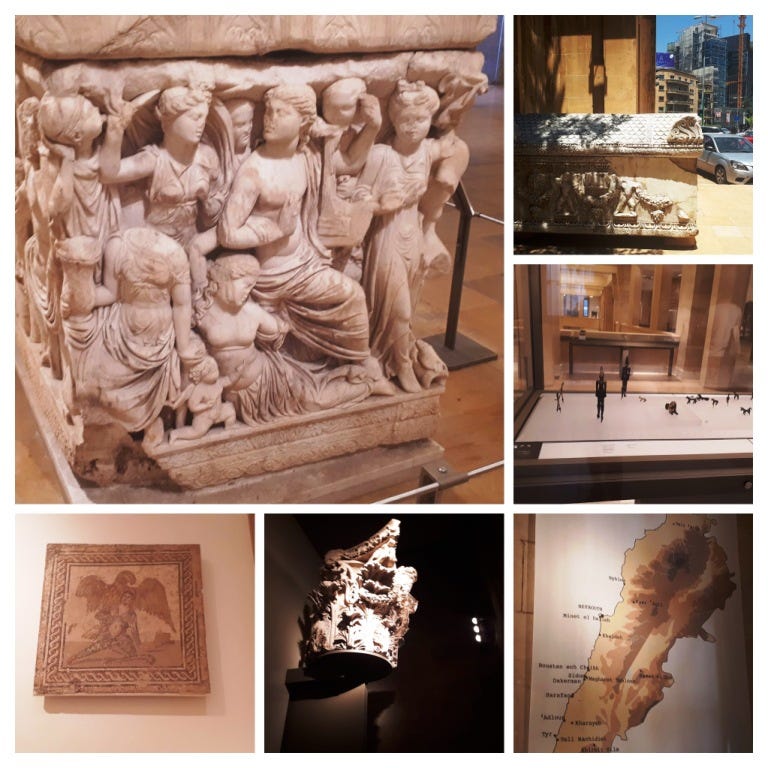

I also visited the Sursock art Museum and the National Museum.

The first tour I did was to the Beqaa Valley to visit Anjar and Baalbek, along with a winery called Ksara.

The day tours included some interesting people, who really wanted to know about the place. I met a Syrian family who drove from Damacus. That was normally one hour, but took five with wartime roadblocks. They said Damascus was safe.

The tour guide knew her stuff. There used to be a railway from Beirut to Damascus, but this was taken out by the 1967 war, so, no public transport whatsoever and a lot of traffic jams.

Anjar is a famous Umayyad city that has an older Graeco-Roman history as well, and a lot of classical ruins with Greek inscriptions and obviously Greek or Roman style. Two palaces, a mosque, and public baths survive in a fragmentary state.

Baalbek was also known in Greek and Roman times as Heliopolis, ‘Sun City’, and it was the site of the largest religious sanctuary in the Roman Empire. Still standing are the ruins of a large temple complex devoted to Bacchus, another one devoted to Jupiter, and a third one devoted to Venus. As the name Baalbek suggests, before that, it as a site where the Phoenician god Ba’al was worshipped. So, Baalbek is actually a really old name predating the Romans and Greeks, which came back into use when the area was Arabised, as Arabic is related to the Phoenician language.

The Temple of Bacchus at Baalbek—Video

The Temple of Jupiter at Baalbek—Video

We also visited the winery and had lunch at Zahlé, the capital city of the district. Oh la, the food was amazing! Hummus, grilled meat, stuffed grape leaves, pastries with cheese in them, and bulgur wheat salad.

To be continued . . .

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!