I RODE the train into Québec City from Montréal, set on exploring the capital of the former New France and the modern Province of Québec; a city so different to most other cities in North America — more like a transplanted plug of old Europe, complete with city walls.

The journey took three hours. I whiled some of it away in a discussion with a Facebook friend who lives in Québec City, a writer of Netflix episodes and aspiring actor who worked on the 2005 film Le Couperet (released as The Ax in America, and The Axe in Britain).

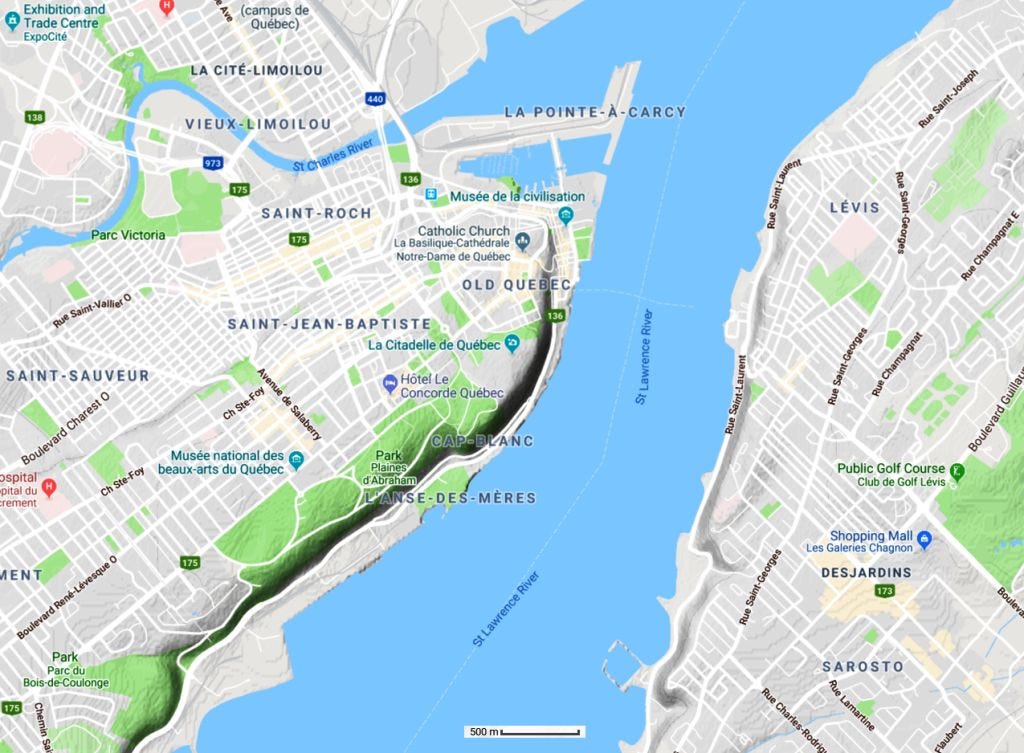

The St Lawrence River was partly frozen over, and so were the cliffs I saw when entering the city of Québec, which stands at the first narrows of the great St Lawrence estuary which leads to the Great Lakes, guarding access to the interior of the North American continent. Or, at least, it did in the days of sail.

I’ll describe my modern adventures in Québec in a moment. But first, a little background on this most historic city.

Québec City was founded in 1608, as the capital of a French colony called New France. The colony itself was founded in 1534 when the explorer Jacques Cartier landed on the Gaspé peninsula, well out toward the east in the St Lawrence seaway. In the maps above, the Gaspé peninsula is a large, curving, peninsula north of New Brunswick, with the town of Gaspé near its tip.

A Canadian national park close to Québec City, which can be seen as a patch of green overlapping the city’s name in the lower of the two maps above, is also named after Jacques Cartier.

Québec City was founded as a fort by Samuel de Champlain: a fort that became the Québec Citadel. All traffic to and from the Great Lakes had to pass through a narrow gut overseen by the Québec Citadel, located atop formidable cliffs that looked down on the St Lawrence River. Cliffs hem in the river in on the other side as well.

Possession of the only way in and out of the Great Lakes helped the French to gain control of what eventually became a vast area of the North American continent. By the mid-1700s, New France extended all the way south to New Orleans and west beyond modern-day Winnipeg, and also incorporated the whole of what is now the mid-western United States. That’s why so many places in the mid-West have French names even though they are a long way from more obvious centres of French culture like Québec or New Orleans.

The northern part of New France was called Canada, the southern part Louisiana. These names survive today, of course, though the boundaries of modern Canada and modern Louisiana are a lot different.

As large as it was, the New France of the mid-eighteenth century was under-populated and hard to defend. Most of the territory had no towns, only forts. If the British could dislodge the French from a few key strongholds such as Québec City, it would be a straightforward matter to take over the rest. The conquest of New France became a British objective once a general European conflict known as the Seven Years’ War broke out in the 1750s.

The British scaled Quebec City’s cliffs in 1759 to capture the city in a battle fought at a site known, in English, as the Plains of Abraham.

Thereafter, Québec became part of British North America and ultimately of modern Canada, in which Québec City is the capital of the Province of Québec.

Ironically, the British conquest of New France made the American Revolution possible. The American colonists didn’t need the British army to defend them from France anymore, and started to think of the redcoats as the enemy instead.

At the same time, despite the loss of the American colonies, the British gained so much territory that they began to talk about something called the British Empire: a rather new and agreeable idea as far as they were concerned.

As for France, it suffered a revolution of its own: a revolution which almost certainly would not have happened had New France not been lost. A dynasty of kings named Louis, after whom Louisiana was named, lost much of its prestige — and domestic instability followed.

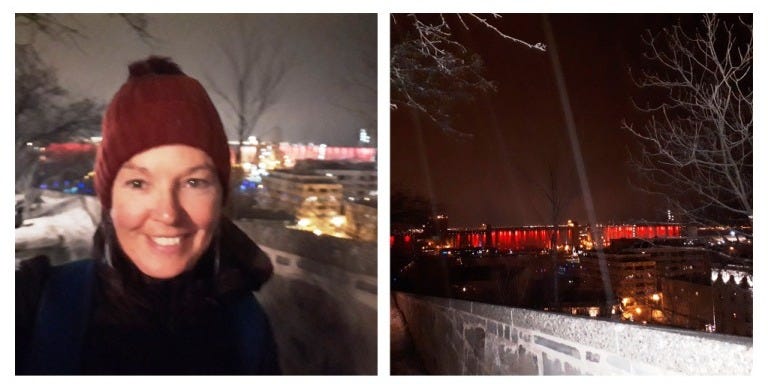

History was made in Québec City once again in August 1943, when Canadian Prime Minister William Mackenzie King, F. D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and the Governor-General of Canada (the Earl of Athlone, in uniform) made plans for the conduct of the latter part of World War II at the Citadel, where the photograph below was taken, and at the Château Frontenac, an upmarket hotel that can be seen in the background.

So, we can say that all kinds of history have been made in Québec, really. It’s not exaggerating much to say that the British Empire, the United States, the French Revolution and D-Day were all made in Québec City.

After I got to Québec City, I stayed in Rue Couillard, at the Auberge de La Paix or Hostel of Peace, which has a peace sign outside.

In the 1970s, locals formed an association to provide cheap accommodation, as the bourgeoisie had objected to people tenting in the green areas around Québec, and the Auberge de la Paix was one of the results.

The Auberge has a large section where people can camp in the summer (in winter it is under a blanket of snow).

The Auberge was a fifteen-minute walk, mostly uphill, from a railway station called the Gare du Palais. This is a beautiful building, one of many that I didn’t notice on the way up the hill due to my heavy backpack with boots in it.

(I intended to use these boots in Nepal, where I was headed next, to go climbing; and was lugging them around with me even in Canada!)

The Auberge was a beautiful building from the 1800s. Maybe, parts of it were older still. But there were a lot of fires in the old days. Buildings were rebuilt to the point that you couldn’t really tell how old they were to begin with.

At the Auberge, you could stay in a dorm or have your own room.

Next morning, I got to know the neighbourhood better. I walked more consciously past the Irish pub called St Pats, past the Hôtel de Ville, the Seminaire de Québec, the Place d’Armes and Parc Montmorency.

I walked along the Promenade des Gouverneurs, which is above the St Lawrence River and as such a bit like the Brühl Terrace in Dresden, and finished at the La Citadelle de Québec, the old fort.

Before I got to the Citadelle, or Citadel, I saw the Château Frontenac, which has long served as an upmarket hotel, and the battlefield known in English histories as the Plains of Abraham. I walked along the fortress walls before arriving at the Citadel.

Motorists who are local stop for you to let you cross the road. I was amazed at how happy they were to do that.

The city reminded me of Edinburgh, with very similar brick and stone houses. Indeed, there was an old alliance between France and Scotland in the days of Mary Queen of Scots, and there may have been some transfer of architectural ideas.

I visited the Hôtel du Parlement, the Québec provincial parliament house, also referred to as the national assembly. You can actually meet local legislators informally — they are so laid back here.

The Citadel is a good example of a well-preserved old European stone fort in the Americas.

What is even more remarkable is that the oldest part of Québec City is also a walled city with the Citadel at one end of the walls. Old Québec is the only intact walled city on the North American continent north of Mexico.

Many Irish also migrated to Québec, to the point that it is estimated that 30 or 40 per cent of the population of the Province of Québec have some Irish ancestry, even if they have French names.

In 1867 the Dominion of Canada was formed from the Province of Canada, corresponding to modern-day Ontario and Québec into which the Province was split, along with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Canada would later add western provinces and Newfoundland, which otherwise remained separate British colonies for a time, indeed until 1947 in the case of Newfoundland.

Section 133 of the Constitution Act, 1867, made the Canadian federal parliament and the Québec legislature both officially bilingual, though the parliaments of other provinces were conducted purely in English. This is interesting, as Māori has also been spoken in the New Zealand Parliament since 1868, for about as long as French in the assemblies of Ottawa and Québec.

The moderate-separatist Bloc Québecois party only hold 30 per cent of the seats in the Québec parliament now, which is dominated by the Liberals. Québec has decided it needs Canada, the guide said.

I went to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, the Québec National Fine Arts Gallery. This featured art both local and international, including some sculptures by the renowned Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti, who worked with Salvador Dalí in Paris in the ’30s, ’40s and ‘50s.

There were also some remarkable paintings, which I haven’t been able to do justice to in the dim light (you can’t use a flash, obviously), but at least these photos give you an idea.

Also, there was some indigenous artwork in the museum, by which hangs a tale:

If the position of the Māori in New Zealand is comparable to that of the French in Canada in some ways, the indigenous peoples of Canada, which the Canadians call First Nations, are in a much more marginal position.

Canadian First Nations have a degree of autonomy on reservations and in various northern fastnesses of a more extensive nature such as Nunavik, the northern third of the Province of Québec.

But Canadian First Nations speak many widely different languages. In New Zealand, all Māori iwi or tribes are united by a common language — indeed, the word Māori means ‘common’ — which is also one of the two officially spoken and written languages in New Zealand, the other being English.

(The Māori name for New Zealand, Aotearoa, land of the long white cloud or bright shining land, also has official status though non-New Zealanders find it hard to pronounce.)

Also, the languages of other Polynesian peoples from tropical islands north of Aotearoa are similar to each other and to Māori, differing only about as much as Spanish might differ from French. Polynesians who come from the tropical islands either directly or by descent are also common in New Zealand today.

To make matters worse for Canadian First Nations, they are a comparatively small minority as well as a scattered one. The population of Nunavik, for example, is only twelve thousand. All the First Nations taken together add up to about 1.4 million out of Canada’s roughly more than 36 million inhabitants.

People of Māori/Polynesian descent add up to about one million in Aotearoa, a number which is smaller. On the other hand, because the total population of Aotearoa is only 4.8 million, the result is a First Nations bloc in Aotearoa that commands a degree of influence that Canadian First Nations can only dream of — a position that is, literally, more like that of the French-Canadians.

A large number of treaties were signed between the Crown or the Dominion of Canada and various Canadian indigenous groups (though not with all of them). In New Zealand there was only one, the Treaty of Waitangi, which is thus perhaps more difficult to overlook.

Though bad things have befallen Māori and their island relatives at the hands of the European, the indigenous populations of Canada have often suffered worse fates, more like those of the Australian Aborigines — and indeed, in one respect, worse still.

The most objectionable aspect of past Canadian indigenous policy is the extent to which indigenous communities were, for a long time, subjected to forced assimilation into white society. A similar a policy was pursued to some degree in Australia with its ‘stolen generations’, but even that was half-hearted by Canadian standards.

Indigenous communities in Canada were even denied formal citizenship unless they abandoned their old ways — no such legal discrimination was practiced in New Zealand, nor even in Australia — and Canadian First Nations also bore the brunt of various other stratagems aimed at wiping out their supposedly primitive tendencies, such as residential schools that broke up families, and even a high rate of forced sterilisation of those judged (by Europeans) to be antisocial or incapable of looking after themselves or their children properly, in the western provinces where indigenous populations were largest.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has been quite busy apologising for all those things lately.

Speaking of Justin Trudeau, he is currently embroiled in a controversy over an oil pipeline that the firm Kinder Morgan wish to build, to transport diluted bitumen from oilfields in Alberta, over the Rockies, to a tanker port in the ecologically sensitive San Juan de Fuca strait north of Vancouver.

There is already one such pipeline, carrying oil, called the Trans-Mountain Pipeline, but Kinder Morgan are proposing a second one to run alongside the first.

The British Columbia government under Premier John Horgan is opposed to the second Trans-Mountain Pipeline, as are a number of First Nation and environmental groups. On the other hand, the project is supported by Alberta Premier Rachel Notley’s government, which is threatening to cut off oil and gas sales to BC if the pipeline doesn’t proceed.

Trudeau is proposing to assert the legal paramountcy of the federal government to ensure that the pipeline goes through and even to bail out Kinder Morgan financially.

I was a little surprised by this, given that New Zealand’s government under Jacinda Ardern has just banned further offshore oil and gas exploration in and around New Zealand (a policy that, admittedly, doesn’t affect current exploration).

But in case readers think I am wandering off topic, the interesting thing about the pipeline dispute is that it has also upset the Québecois, who might not otherwise have taken too much interest in goings-on at the other end of the country.

For the Québecois guard their autonomy and special character dearly, and don’t like to see the federal government getting too heavy-handed with a province whatever the issue might be.

I had a massage at a place called L’attitude by a woman called France, who said if I meditated my back pain would go away and practiced the Trager massage technique. But I would not recommend it, as it isn’t hard enough for my back pain. This was in the fashionable Avenue Cartier District.

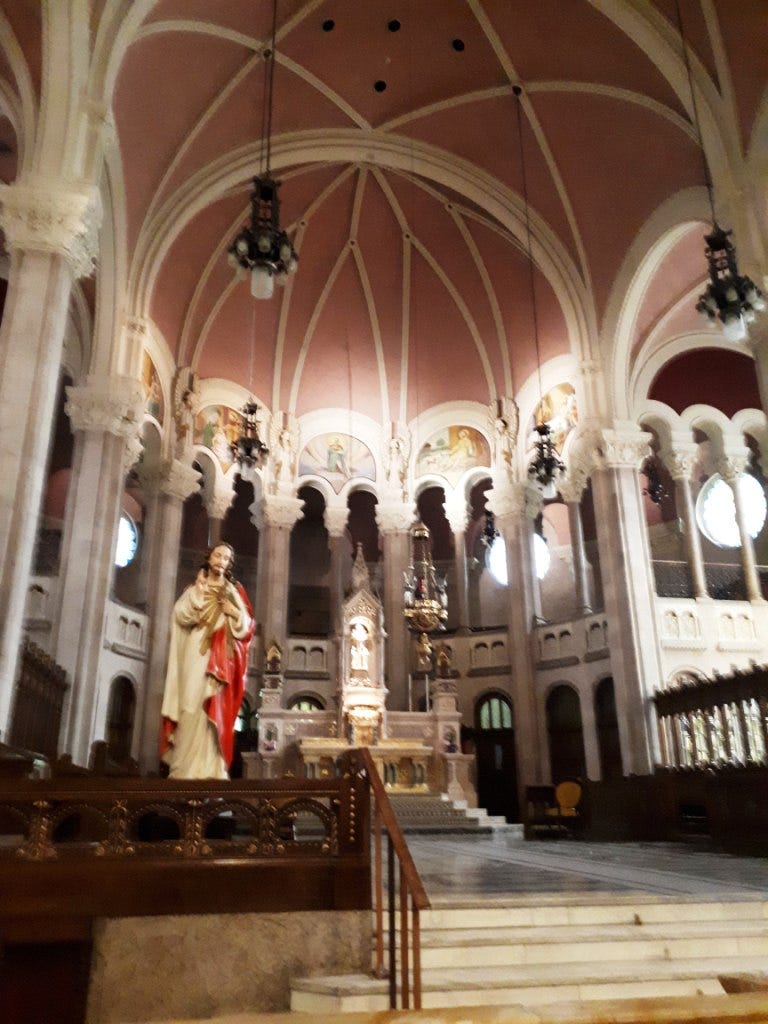

As to where people should stay, I recommend the Saint-Roch district, northwest of the old walled city. Saint-Roch has a Youth Hostel and is, most importantly, outside the city wall. The issue is that the old city is more picturesque, but parking inside the wall is hard to find. The district is unmissably dominated by a large, early-twentieth-century Roman Catholic church, the Église de Saint-Roch.

I wanted to do a further walking tour with a proper guide, but Trip Advisor had nothing under $300, so I downloaded a free self-walking app. The Bureau de Tourisme offered some local advice, but also told me to go online to find out about le Parc national de la Jacques-Cartier, the Jacques Cartier National Park.

The Jacques Cartier National Park is forty minutes from Québec City and is great for both Winter and Summer sports. You can hire snow shoes, and other items in Winter and do a tour. You can stay in cabins and yurts. It’s worth checking the website sepaq.com/jacquescartier (exclusively in French, but it’s easy enough to auto-translate).

I hired a car in order to drive to the Jacques Cartier National Park. What with global warming and the paradoxical increase in cold snaps that it causes in mid-latitudes, the result has been an unusually cold April. So, I had snow tyres. Which was just as well because when I finally left Québec City for the airport, once more by car, it was in a blizzard!

I had a connecting flight to Montréal, and then to Toronto. But these didn’t happen thanks to the storm, and also thanks to what I though was the incompetence of Air Canada, who proceeded to lose my luggage.

I got to Montreal OK, but then it turned out my 5:45 flight was cancelled. They put me on an earlier flight, at 4:30, and my bag, with all my heavy and expensive gear for Nepal, somehow failed to turn up on the carousel at Toronto.

I was given a toothbrush and told that it would turn up the next day at Montreal, but it didn’t. Meanwhile I was booked onto a connecting flight to Los Angeles, so I could make my flight to Nepal.

In the end I had to press on to Nepal and get more gear once there. My bag was sent on to Auckland, where it did arrive, by the Canadians. I felt that I got no sympathy from customer service and gave them 3 out of 5 on Google.

Here is my Amazon author page. I’m also publishing my books, progressively, on other platforms.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!