AT THE beginning of October 2017, I stopped off for two nights in Doha, the capital city of the the small Persian Gulf state of Qatar (and its only sizeable city). Travellers from New Zealand often choose to break the long journey to and from Europe in Bahrain, Qatar, or in the nearby United Arab Emirates,

Long a refuelling-stop for airlines based in other parts of the world, the oil-rich region now has several well-known airlines of its own: Qatar Airways, Emirates, and Etihad.

While I was taking a break in Doha, I also took quite a few photos. I’ve also included a video of constantly changing Islamic designs, in a fascinating light-show which I saw inside Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art.

I was especially keen to visit Qatar because of the recent boycott by Saudi Arabia, which closed Qatar’s only land frontier in June 2017. Four Arab states, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain, have boycotted Qatar since then. They accused Qatar of destabilising the region via its support for many of the protesters in the Arab Spring movement of 2011. Qatar was served a humiliating 13-point ultimatum, which it promptly rejected. Among the thirteen points, the one that seems most extraordinary is a demand for the closure of the well-known Qatari state broadcaster Al Jazeera, which has often been described as the BBC of the Middle East.

Much as in Thailand, the media in Qatar are not allowed to criticise the ruler himself, the Emir. But they are free to get stuck into anyone else. Neighbouring rulers, who have been regularly criticised by Al Jazeera under what they see as a double standard, want to see Al Jazeera closed down.

I wanted to see how Qatar was coping under the boycott.

Qatar has a population of 2.6 million, most of whom are foreign guest workers and their families. Only a little over 300,000 people in the country are Qatari citizens. The capital, Doha, is halfway along the east coast of Qatar, a peninsula with only one land border, the border with Saudi Arabia.

Qatar has a long history. It was known to the ancient Greeks and Romans, who spelt it with a K and a C, respectively. It was ruled by various Arab rulers for centuries, and then from 1871 until 1916 by the Ottoman Turks. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Qatar and the Emirates became part of the British Empire. They were subject to a form of semi-colonial rule in which the British stationed troops locally and agreed to to defend them from attack in return for their not hosting troops from any other country.

In 1968, the British decided to bring home all troops stationed ‘east of Suez’ in order to save money. The policy was upheld until the first Gulf War in 1991. No more Tommies east of Suez meant that the Persian Gulf protectorate was finished. And so, Qatar and the Emirates became fully independent in 1971.

Traditionally, Qatar was a quiet place where a small population made its living from that most romantic of pursuits, pearl diving. The pearl is still a symbol of Qatar in some ways. But the discovery of oil and gas changed all that, and ensured for better or worse that Qatar would no longer be a backwater.

For one thing, like Kuwait, it was now coveted by its neighbours. A precariously independent Qatar must do the splits, diplomatically speaking, between nearby Saudi Arabia and Iran just across the water. With the British gone it hosts new military bases, both of the United States and of its former overlord Turkey (the splits, once again).

Qatar is also the first Arab nation to be hosting a FIFA World Cup football tournament, in 2022. Just lately, a a link has been made between the blockade and the World Cup. It seems that if the Emir won’t accede to the original ultimatum, then Qatar giving up the World Cup might be the new price for ending the blockade.

I ended up staying in the area of Doha known the consular district, in the West Bay Lagoon area. This was some 30 minutes from the airport. I stayed in Airbnb accommodation with a huge and amazing room and a large double bed.

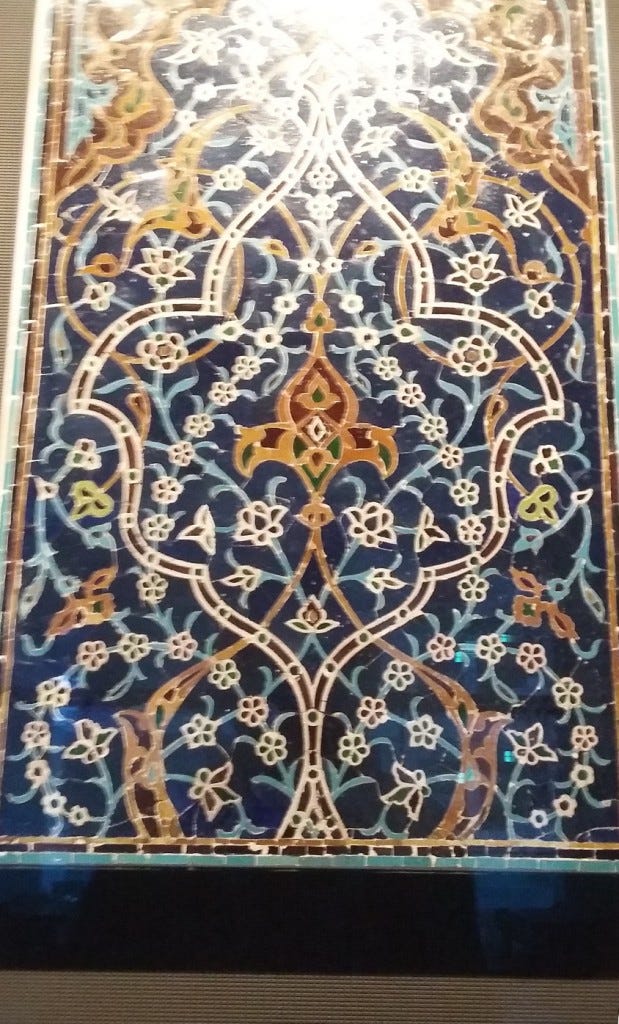

I went to the amazing Museum of Islamic Art: a form of art noted for its emphasis on calligraphy and abstract and floral designs. The museum described the cultures of various nationalities in the Islamic world: people such as the Kurds, Mughals (responsible for the Taj Mahal), Arabs, Persians, Turks, and the Uighurs from western China.

For the concerned female traveller are taxis aplenty (though not all of them well-regulated). And security guards of a sort that I found reassuring are everywhere as well.

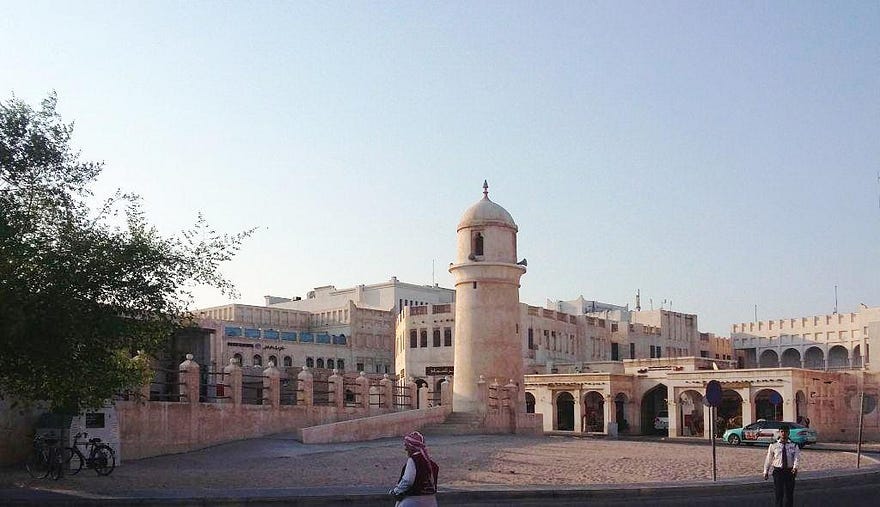

I went to the markets, and enjoyed beautiful Arab food in the Old Market. On the shore I saw the dhows, which still ply these waters as in the days of Sinbad.

The main tourist season is winter and early spring, when cold desert nights make the mornings cool and crisp. When I was there it was about forty degrees C. And that wasn’t the hottest time of the year!

Although Qatar is wealthy enough to weather the blockade, it is starting to tell. There has been some inflation of food prices.

Qatar is unquestionably an Islamic country, though its guest workers practice a variety of faiths and non-faiths. It lives under a mixture of of a more lenient civil code and a strict form of Sharia law similar to that of Saudi Arabia. For instance,its attitudes to alcohol are basically prohibitionist, with one or two loopholes. There is only single street-front liquor store in the whole country, serving only non-Muslims, who must have a permit to prove it. And there is an exemption for discreet consumption inside tourist hotels as well.

So, the system in Qatar is similar to Saudi Arabia in some ways, but with a greater degree of live-and-let-live in practice. Literally so in some cases, for, in contrast to Saudi Arabia, nobody has been executed in Qatar this century. On the other hand, floggings continue. The last few Emirs have been modernisers, but, in this area as in others, it seems that Qatar has to do the splits — as I’ve put it.

I did not run into any cultural obstacles to a single Western woman travelling alone. In contrast to Saudi Arabia, once more, women have long been allowed to drive in Qatar. And in contrast to both Saudi Arabia and Iran, women are not forced to wear Islamic head-coverings in public.

might add that the custom of female head-covering is not strictly Islamic. It is really just an old custom, which persists in the Middle East after having died out in Europe. In Mediaeval art, in Pieter Breughel’s paintings of the Flemish peasantry and in photos taken around the time of World War One, Western women nearly always have their heads covered, with a scarf or shawl if nothing else. The trendsetting Princess Grace of Monaco hardly ever went out without a head-scarf. And Western men didn’t give up wearing hats either until the 1950s, as we know.

Still, without being overly prescriptive, ‘modest’ dress is expected in Qatar.

People in Qatar are generally well off in material terms, and Qatar is also the fastest-growing Gulf State these days. On the other hand, there is a lot of lovingly-preserved architecture, and some modern buildings have been done in old-fashioned or distinctly Islamic styles. In one of the pictures above the townscape even looks like ancient Greece or Rome: architectural neoclassicism taken to the logical limit.

Last but not least, here’s that projection I mentioned, using an old-fashioned technique based on glass plates called gobos; see this link on how it was done.

In parting, I would say that I wish that I had acquired a Qatari SIM card for my phone. And also, that I had taken legitimate taxis rather than dodgy informal ones with inexpert drivers, such as the one I took that got stuck in the sand. That sounds like something of a Middle Eastern cliché, but it did happen.

Here is my Amazon author page. I’m also publishing my books, progressively, on other platforms.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!