ONE place I never get tired of visiting is Melbourne.

The capital of the Australian state of Victoria, Melbourne lies on a vast natural harbour called Port Phillip Bay.

On the same latitude as Hamilton, New Zealand, Melbourne is also the southernmost and coolest of the five big cities on the Australian mainland.

So, Melbourne is mostly quite mild and pleasant. It is also a ‘garden city’. In this 3D aerial image from Google Earth, you can see how true that is.

Here’s a closer look at the very heart of downtown:

Melbourne’s an intensely walkable city. The next couple of photos show the Rainbow Pedestrian Bridge over the Yarra River, with countless pedestrians crossing it at dusk. Underneath the bridge is one of the world’s smallest islands, Ponyfish Island. The island is entirely covered by an outdoor bistro bar, at which some of the pedestrians tarry!

I will be writing about my visit to Melbourne a little further on below. But first, let’s take a look at the city’s colourful history.

Melbourne was founded by the Crown in 1836, following the dubious acquisition of its site by a private adventurer named John Batman in 1835. Batman hailed from Tasmania, then known as the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land. According to a neighbour, the artist John Glover, Batman was a “a rogue, thief, cheat and liar, a murderer of blacks and the vilest man I have ever known.”

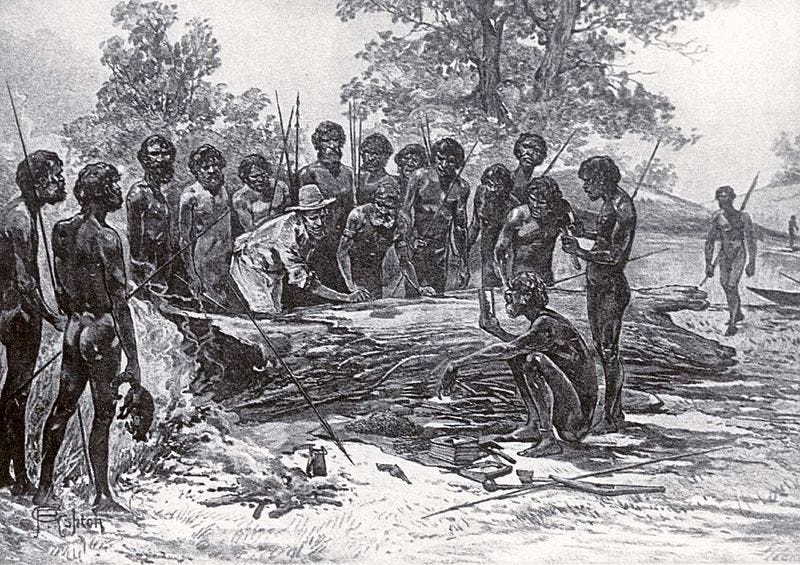

Intent on founding a colony of his very own, to be called Batmania — a possible clue as to the wider soundness of his judgement — Batman claimed for the rest of his days that he had obtained 600,000 acres of land from people on the mainland, called the Kulin. According to Batman, this estate was leased to him in return for an annual tribute of goods, including several dozen knives, shirts, blankets and hatchets.

Batman and his party could not find an interpreter and were thus reduced to conducting the negotiation in sign language. It most unlikely that the Kulin understood the transaction in the same, permanent, terms as Batman. But as one later historian noted, “No doubt the blankets, knives, tomahawks, etc., that he gave them were very welcome.”

Batman’s land claim was immediately annulled by the Governor of New South Wales, Richard Bourke. The Governor moved swiftly to establish an official settlement on the same site with the more sensible-sounding name of Melbourne. Bourke’s settlement was named after the British Prime Minister of the day, Lord Melbourne, whose party Bourke openly favoured. A few years after his attempt to found Batmania and the official founding of Melbourne, Batman died of syphilis; a disease that may have accounted for the grandiosity of his scheme.

As incredible as it might sound to a New Zealander, arrangement with the Kulin arrived at by the rogueish and quite possibly deranged John Batman — sometimes dignified with the name of Batman’s Treaty — is the only recorded instance in which European settlers actually negotiated with Australian aborigines for access to their land. Others, including Governor Bourke, didn’t even bother.

And so, the city that grew up in the former Kulin territory was called Melbourne, created by a high-handed stroke of the Governor’s pen in 1836, and not Batmania.

2. The Rise of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’

After the town was founded, as the capital of a new colony of Victoria hived off from New South Wales, it grew rapidly. Within a decade Melbourne was half the size of Sydney, founded much earlier in 1788. People took to calling the fast-growing Victorian city ‘Marvellous Melbourne’.

Here’s an 1861 painting of the solid city as it had become, only 25 years after its foundation in 1836. This picture, showing the original Princes Bridge, is painted from a viewpoint similar to the modern-day image of Flinders Street Railway Station and St Paul’s Cathedral above, through from ground level rather than the air.

In 1885, the most prominent church in this painting, St Paul’s Church, behind a house that is in shadow, was torn down to make way for St Paul’s Cathedral; but even St Paul’s Church was pretty impressive!

By the 1890s, Melbourne contained half a million people, a grand exhibition hall, a great network of railways and smoking Victorian factories churning out the iron and steel for more rails and the iron lace of Victorian townhouses; and yet there were still oldsters who remembered the site of the city as nothing more than a level plain.

After this initial period of fast growth, however, Melbourne’s growth tapered off, and it never succeeded in catching up with Sydney. During the twentieth century, Melbourne would always play second fiddle to its brash New South Wales cousin. Between 1901 and 1927 Melbourne did have the distinction of being the capital of the new Australian federation.

After Canberra became the capital in 1927, Melbourne became firmly stuck in second place, and even began to acquire a reputation as a city that was a bit slow, rather than fast-growing (though it was still the second-biggest city in Australia).

In compensation, Melbourne began to claim to that it was somehow a better place to live than most other parts of the country, its way of life a happy medium of town and country principles: a ‘garden city’

Whether people were speaking of a brash and Americanised Sydney or dusty regions of the Outback, Melbourne was held to be a cut above all those sorts of places.

3. Melbourne Today

So, what is Melbourne like today? Well, the short answer is that it is a real city. The central area is a delight to wander about in and be a tourist, with free trams since the beginning of 2015.

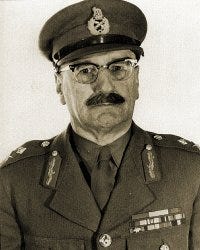

And of course, Melbourne did retain its trams when other cities were tearing them out half a century ago, courtesy of an unorthodox head of the local board of works, Major-General Sir Robert Risson, who declared that “transportation is civilisation.”

The usual rationale for getting rid of the trams was that they made it hard for cars to get into the central city. The trams hogged the middle of the road and were hard to overtake. Well, if by retaining the trams Melbourne succeeded in discouraging bogans in Holdens from cruising up and down Bourke Street, that was just fine as far Sir Robert was concerned!

Risson’s attitude was typically Melburnian. There is something old-fashioned and slow-paced about the city, a certain something which goes beyond the obvious fact of the retention of the trams. There is a massive area of beautiful parklands along the Yarra River and in the inner suburbs, which makes Melbourne a true ‘garden city’.

Thousands of people are moving to Melbourne each year from Sydney in the hope of finding a place where they can live, rather than exist.

Ironically, there are many people who fear that fast growth — once more a feature of Melbourne life — may imperil the values that attract immigrants to Melbourne in the first place.

At the same time, there is a lot that is modern and go-ahead. The urban train service has been progressively improved, with a circular City Loop rail tunnel excavated under the CBD in the 1980s, and a new Metro Tunnel about to be built between the suburbs northwest of the CBD and those to the southeast, near St Kilda.

And exciting modern architecture exists everywhere. One thing that is very noticeable is that the dull, grey, industrial-looking aluminium cladding that seems to sheathe every second building in downtown Auckland, including the Sky Tower, seems to have been banned in Melbourne.

Maybe they still use this kind of cladding. But if so, it clearly has to be some colour other than grey. That seems to be the planning rule in Melbourne: either that, or it’s a point of pride that the building owners uphold themselves.

Modern eco-building with plants growing up the side for shade

The only real negative for Melbourne, as for most of the rest of urban Australia and New Zealand, is the ridiculous cost of housing. This is a problem that could be solved if the political will was there, but obviously it isn’t.

In this respect Melbourne has become the kind of big city once described by the urbanist Hugh Stretton, in his book Ideas for Australian Cities, as “physical and psychological devices for quietly shifting resources from poorer to richer and excusing or concealing — with a baffled but complacent air — the increasing deprivation of the poor.”

4. My Impressions

I flew into Melbourne from Tasmania, where you could get houses for as little as A$20,000, but where the bottom had lately fallen out of the important local mining industry, as in many other parts of Australia.

I hadn’t been to Melbourne for a quite a while, so I was keen to see the city again. I was scheduled to stay for nine days. I stayed with some people at an Airbnb close to Southern Cross Station for A $60 a night; they took me out for breakfast and showed me the markets.

They had paid A $500K for a 2-br apartment; the cost of apartments in Australia is ridiculous and high construction costs seem to have something to do with it, the price is twice what you would pay in many American or Canadian cities. I met people who were renting one-bedroom apartments for A $350 a week. Even so, these housing costs are quite a bit cheaper than in Sydney, which is now held to be the second most unaffordable city in the world, after Hong Kong. About 500 people a week are moving to Melbourne from Sydney, and when immigrants from other places are added in as well, the population of Melbourne turns out to be increasing by about 100,000 people a year. It is currently 4.6 million, and it increased by one million in the space of only twelve years, according to a recent report. Official projections are for 8 million Melburnians by 2050 or so, if the city does not somehow burst at the seams before that.

The unexpected highlight of my tour was a visit to the Victoria State Library. It had an impressive, domed, reading room with leather-covered desks, and the staff gave free tours around a museum section.

Our tour started on the 1st floor and the tour showed the history of Melbourne, how Melbourne had waves of immigration, Greeks and Italians arriving in the central city after World War II. There were extracts from the diary of May Stewart, an ordinary young woman around 1906, which showed the everyday life of Melbourne in those days. There was a Ned Kelly section which showed why he had become desperate, it was to do with Irish politics and being harassed. They had a plaster death mask, which I will not show here as it is too macabre.

There is also a separate Immigration Museum in Melbourne. This museum really brought out the misfortunates of current refugees and migrants, whose position makes me wonder if Australia is returning to the old White Australia policy in some ways. At any rate it is obvious that the refugees are somehow the scapegoats for wider community concerns about the rate of immigration to Australia and the population growth and general urban strain on infrastructure and housing that comes from it. The official rate of immigration to Australia is 190,000 a year, which is quite modest relative to an overall national population of a bit over 24 million.

However, just about all the immigrants come to the major cities, and on top of that, there are about two million people living in Australia on temporary visas, including more than half a million New Zealanders. Critics allege that Australian political class has used immigration to stoke the big-city housing markets where presumably they and all their friends have investment properties, and also to keep the country technically out of recession, since with high levels of immigration economic growth is unlikely to turn negative, no matter what. Meanwhile, genuine refugees have become the meat in the sandwich, victims of a symbolic crackdown against a particularly vulnerable class of immigrant who, of course, brings little money into the country.

On a more cheerful note, there is a lot of ornate old Victorian architecture still, such as the Royal Exhibition Building from 1880, the Melbourne Town Hall and the famous Flinders Street Railway Station.

In terms of some of the newer architecture, the South Bank of the Yarra, and the Docklands were both impressive. While on the South Bank, I went with some friends to Ponyfish Island, which I’ve mentioned above.

Also way-out is Federation Square, on the north side of the Yarra and close to the Princes Bridge, across which many of the trams go across, including the trams that run to Melbourne’s famous St Kilda Beach and several other seaside destinations. You can see a bit of Federation square in the second image right at the start of this post.

I never made it to St Kilda beach, but I still want to go there. And another thing I need to do is to go for a ride in the Colonial Tramcar Restaurant, which trundles around the streets of Melbourne in a tram fitted out as a dining car.

Here is my Amazon author page. I’m also publishing my books, progressively, on other platforms.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!