BACK IN BEIRUT, I got to know some more people at the Meshmosh Hotel. For instance, there was an American marine insurance rep who said he lived in Hong Kong and his wife was Moroccan — a multi-cultural household if ever there was one!

The American said that he went to a war museum run by Hezbollah, the powerful Iranian-backed political-cum-paramilitary organisation, which has members in the Lebanese parliament and two cabinet ministers. Hezbollah also runs a militia that many say is more powerful than the actual Lebanese army.

Hezbollah used to be very extreme in its early days and was clearly identified with the most militant wing of Shi’ite branch of Islam as personified by the Ayatollah Khomeini. More than thirty years on Hezbollah is thought to be more moderate, though it remains very heavily armed and is currently taking part in the fight against ISIS.

The American guy said that he saw a lot of captured Israeli weapons at the Hezbollah war museum. He had to pay to get in and complained to us that Hezbollah were still a registered terrorist organisation in his own country (which is true), so he felt bad about dropping money in the box.

Back at the hotel I also met Demetri; a Greek guy who left at the beginning of the Civil War as his father had lost his job and everything. Most of Lebanon’s Orthodox Greeks still live there, however. The American planned to spend another three days driving around Lebanon and had room in the car for anyone else who was keen. I asked Demetri whether he wanted to go, and we all agreed to set off together. I describe some of the place we went to further on below.

The American was brash and really opinionated. Demetri and I wondered how he’d managed not to get into some kind of trouble with the Hezbollah. That was our only reservation about the tour.

Meanwhile, I made sure to visit all the mosques and churches in downtown Beirut. The new Sunni mosque had the women’s prayer area in the main part of the mosque. In the old mosque the woman had to look at the main area via a television screen. So, things are obviously changing.

(When we got to Baalbek, I wanted to go inside the beautiful Shi’ite mosque there but wasn’t able to as it was a Friday — the equivalent of a Christian Sunday, of course — and strictly for the actual congregation on that day.)

When I read about the car bombings here I was scared; but I believe there have been more in France. Then again, France is a much bigger country! The Lebanese Army troops who patrol Beirut and check under the cars for bombs seemed friendly enough and spoke a lot of English. I relied on them quite a bit for directions.

My GPS didn’t work in Lebanon, and it was a good thing Demetri had come along, as he was able to speak Arabic and was able to ask the villagers for directions. I suppose we could have bought an old-fashioned paper map somewhere, but you rely on technology these days and then when it doesn’t work you are left to your own devices.

There were supposed to be 10,000 United Nations peacekeepers in Lebanon still. But we didn’t see any blue helmets anywhere in the borderlands, and Demetri — the only one in the car with local knowledge — seemed to be quite nervous about that.

Demetri and I went to the Hezbollah war museum, the Tourist Landmark of the Resistance, which is near the village of Mleeta, just under 20 km from the Israeli border.

In the disturbed days of the Lebanese Civil War and its aftermath, Israel occupied these southern borderlands and turned Beaufort Castle, which is also in this region, into a modern army fort. I talk about that that in my first post on Lebanon.

Mleeta is slightly outside the 1982–2000 occupation zone, most of which lay between the western section of the Litani River and the Israeli border.

A video I filmed inside the museum

The PLO, Hamas, and other Palestinian organisations need to be distinguished from Hezbollah, which is Lebanese. These organisations are divided by religious confession and also by ethnic distinctions invisible to most Westerners, who fail to realise that the Arab peoples are in fact almost as diverse as the inhabitants of Europe.

Hezbollah is a Lebanese organisation that is also associated with Shia Islam. The PLO is Palestinian and secular. Hamas is Palestinian and Sunni.

From the 1960s until 1982, there was a strong PLO presence in southern Lebanon, and from 1976 until 2005 the Syrian army was also an occupying force, until a revolt by the Lebanese (the ‘Cedar Revolution’) forced it to leave.

The Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon, which was fully in force from 1982 to 2000 and which I mention in my first blog, was largely undertaken in response to Syrian and PLO activity, which included the firing of rockets into Israel. Hezbollah gradually took shape with the aim of getting the Israelis out of Lebanon.

Demetri and I interviewed a spokesperson for Hezbollah named Moussa. It was interesting getting a Hezbollah view of Israel. Moussa said that Hezbollah had destroyed at least 130 Israeli Merkava tanks during a later conflict in 2006. The Israelis apparently concede the loss or temporary disablement of 52 Merkavas in that war. Either way, Hezbollah were generally able to inflict more damage than Arab guerillas had been capable of hitherto. An elaborate defensive system of tunnels was developed, from which Hezbollah fighters would pop up, shoot at Israeli targets, and then vanish underground.

Moussa said that the aim of all this was to keep the Israelis from permanently occupying or colonising the southern Lebanese borderlands in the way that they had done with the Golan heights and parts of of the Palestinian West Bank. To keep the Israelis out, Hezbollah had had to become a more serious military force than the old-time PLO.

He insisted that Hezbollah’s military purpose was primarily a defensive one: to keep the Israelis out of south Lebanon by making the costs of any future occupation too high. Here’s the interview, slightly edited, in two parts.

The Hezbollah museum was indeed full of captured Israeli weapons and also some old ones that had belonged to Hezbollah. It was opened in 2010, on the tenth anniversary of the Israeli departure from the area, in a ceremony attended by representatives of the Lebanese government and the left-wing American intellectual Noam Chomsky.

Later on, in Israel, I ran into an ex-Israeli soldier in Tiberias (i.e., Galilee), who had fought in the area of Beaufort and Mleeta. He was pretty amazed that I’d been to south Lebanon even though it’s quiet these days — more or less, and for the time being.

Gosh, I appreciate the rights to a quiet life that we have back home.You have no idea.

It was after I’d been to the museum that I visited Beaufort Castle. From Beaufort you can see the road to Damascus and the Golan Heights: clearly a strategic spot, every bit as much today as in Crusader times.

In terms of military history, there’s obviously a lot of the ‘same old same old’ in these parts. Pretty much every strategic valley and pass has been the site of repeated battles from Biblical times to the present day.

The sites of old battles remain the potential sites of new ones in the Levant: as the easternmost shore of the Mediterranean is known in its totality, from Hatay to Gaza. The Lebanese-American poet Kahlil Gibran, who I’ll have a bit more to say about below, wrote a line about the dead preparing the world to become a tomb for the living, and that very much applies to a part of the world where new battles are fought in the old locations.

When will Beaufort be just a tourist fort like the Québec Citadel and Fort Ticonderaga near the nowadays undefended US-Canadian frontier; or like all those historic forts that still dot the line, similarly, between Germany and France?

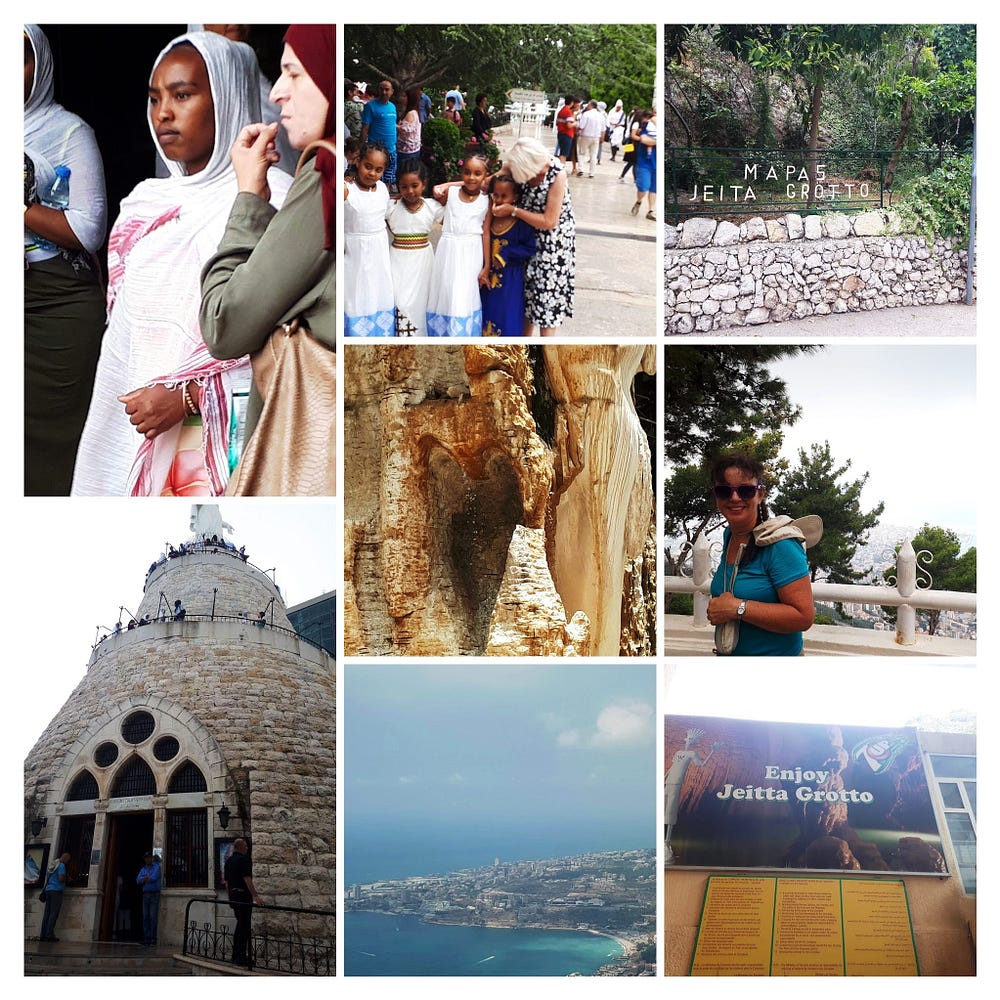

After visiting the beach at Tyre, and touring the south and the Beqaa Valley, I joined a tour northward from Beirut to the Jeita Grotto, Harissa, and the ancient but still-populated city of Byblos.

This tour had four United Nations people on it helping the Palestinians in camps. There was also an Egyptian woman who told me about the number of illegal immigrant workers from Ethiopia in Lebanon: people who weren’t protected in any way from exploitation and abuse.

Harissa is the site of an important ‘Marian’ shrine, that is, an area sacred to Mary, the Mother of Jesus. The site is important to both Christians and Muslims, since Jesus and Mary feature prominently in the Qur’an too, and apparently more often than in the New Testament. So perhaps on that count we should reverse the order and say that you can read about Jesus and Mary in the Qur’an, and ‘in the Bible too’!

Together with a nearby monastery, there are two main religious complexes specifically dedicated to Mary at Harissa: Our Lady of Lebanon, which is often rendered in French on the maps as Notre Dame du Liban, and Sayidat al Maounat, which means Our Lady of Assistance. They are both run by the Maronites. There is also a nearby restaurant called Maria’s (no comment!).

From high places in this locality you can see Beirut and the urbanised coastal Riviera that stretches northward from the city centre to the Bay of Jounieh and beyond. A large statue of Our Lady, the most prominent Harissa landmark, looks out over the city’s northern suburbs.

In Harissa, I saw about two thousand woman all dressed in white with headscarves. I thought they were Muslims at first, but it turned out that they were Ethiopian Coptic Christians on a pilgrimage. Clearly Harissa was extra-important to this immigrant minority.

I had already met three Ethiopians who worked in the kitchens of the Hotel Meshmosh. They were treated well there, but others not so in private homes: modern slavery all over again.

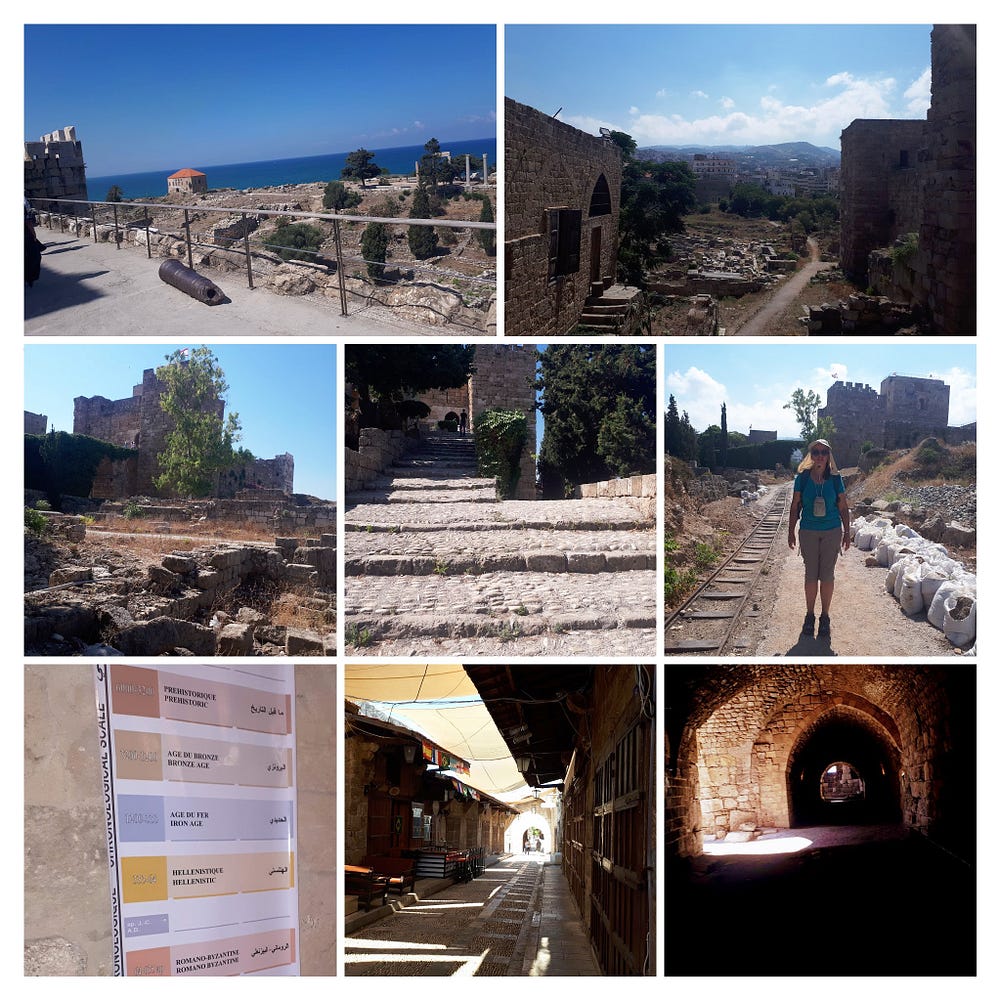

The city of Byblos is thought have been first occupied first 8800 and 7000 BCE. The site has been continuously inhabited since 5000 BCE, making it one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world.

According to fragmentary writings attributed to an ancient Phoenician priest Sanchuniathon — the Phoenicians wrote on parchment, and almost all their literature was ultimately lost — the city was founded by a god named Cronus and was the first city in Phoenicia.

The Phoenicians were a Semitic people, called Canaanites in the Bible, which means that they were related to modern Arabic and Jewish communities as well as to the various modern Middle Eastern minorities who speak Aramaic, itself one of the oldest spoken languages on earth.

(Aramaic is the language Jesus is supposed to have spoken. Aramaic has remained a continuously spoken language to the present day, unlike Hebrew, the official language of Israel, which declined into the status of a ‘language of scholarship’ during the Jewish diaspora before getting jump-started as the language of a new nation.)

The name Phoenician comes from an ancient Greek word for purple (it’s not what the Phoenicians would have normally called themselves), and refers to the fact that the Phoenicians, who were also a seafaring people engaged in trade throughout the Mediterranean, controlled the supply of the purple dye made from sea-snails which was used to dye prestigious articles such as — in later times — the togas of Roman emperors.

I say ‘in later times’ because by the time Rome became an empire, the last major stronghold of independent Phoenician power — the city of Carthage, and its empire — had been destroyed by the forces of the earlier Roman Republic.

Though the city of Carthage was far to the west, in modern Tunisia, Phoenician civilisation nonetheless originated in the Levant and in fact, if the legends are to be believed, in Byblos.

The other great claim to fame of the Phoenicians is that they came up the oldest verified alphabet. Their alphabet, which contains letters we would recognise as forerunners of our own — if we look hard enough — evolved in one direction toward the Greek, Cyrillic (‘Russian’) and Latin or Roman alphabet (the one now used to write English, French, etc), and in another direction toward the Aramaic, Hebrew and Arabic forms of writing.

The Jeita Grotto, which I also visited, contains two huge caves full of stalactites and stalagmites. The caves are called the upper and the lower cave. You can walk through while the lower cave can only be traversed by boat. I took a gondola — it was amazing! I couldn’t take photographs as the light was a bit dim and I only had a smartphone. But there are some great pictures of the grotto on its official website, jeitagrotto.com .

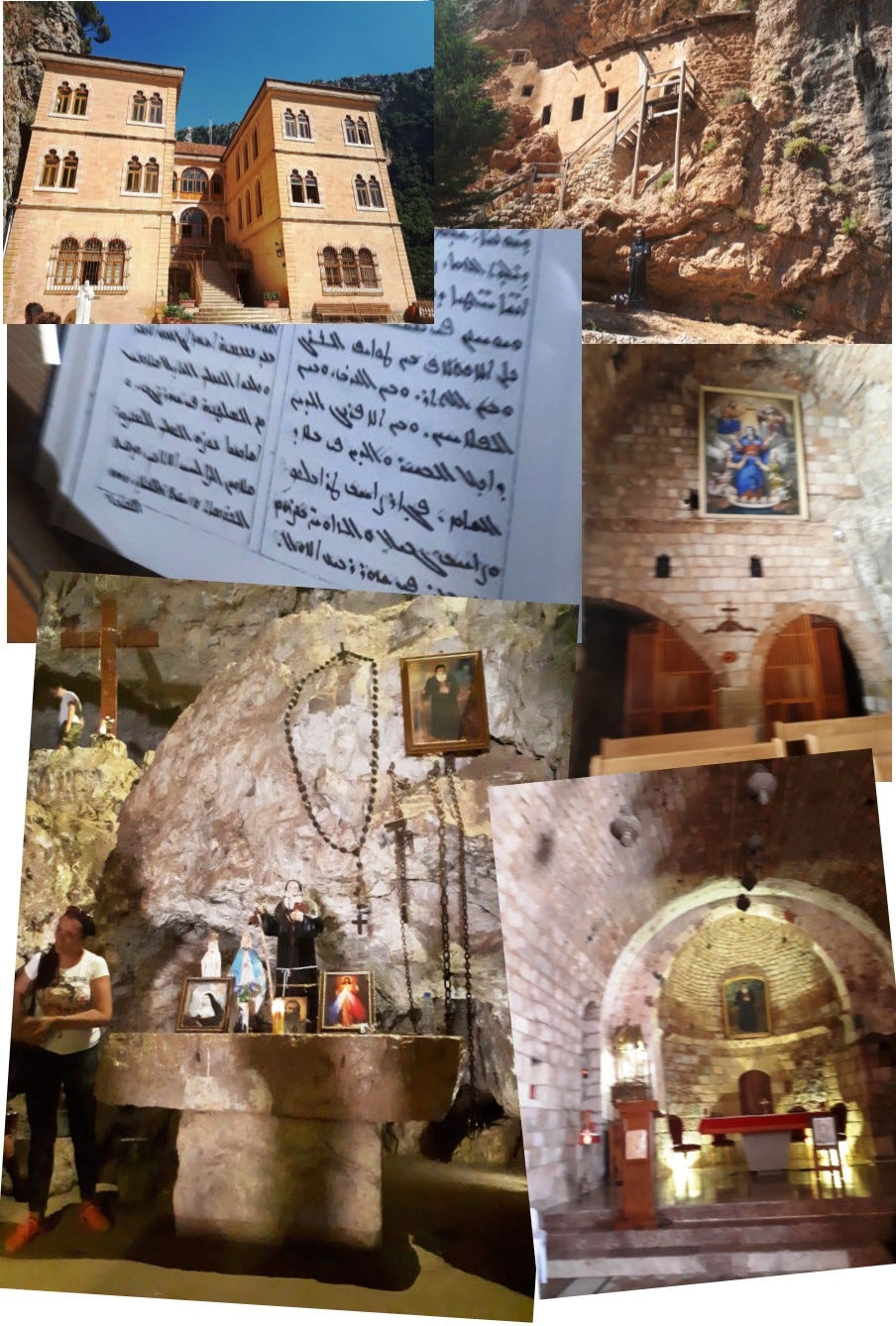

I then went on another tour in northern Lebanon, to the Qadisha Valley. Qadisha means ‘Holy’ in Aramaic and is related to words like the Hebrew ‘Kaddish’, a prayer for the dead. The Qadisha Valley contains the tombs of Phoenician kings, so I suspect it is one of those holy places in the Middle East that is still considered holy but where the holiness actually predates modern religions. I came across one or two places of that sort earlier, in Hatay.

Pots are put on the rocks here if couples become fertile. This custom is supposed to predate Christianity and Islam.

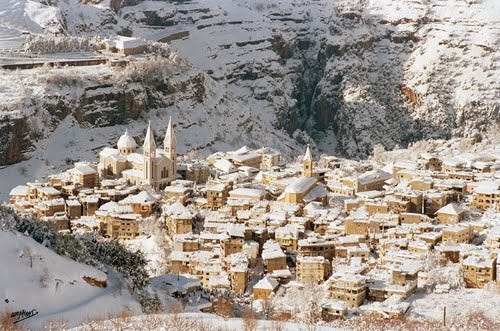

The valley is located near the village of Bsharri (or Bcharre) at the foot of Jabal al-Makmal in northern Lebanon, the highest part of Mount Lebanon. Mount Lebanon is actually a range that stretches for a hundred kilometres or so: the terminology is confusing!

This tour had a guide who was amazing. She was Maronite and knew the country’s history ever so well. And there was a Palestinian woman who lived in London, with her black robes on jumping up and saying she loved history in the Maronite church. Now that just undid all the stereotypes.

There is a cedar grove in the Qadisha Valley called the Forest of the Cedars of the Lord (or, of God), which sits all alone and forlorn in an otherwise deforested landscape. Some of the individual trees may be a couple of thousand years old, or more.

A video I filmed among the Cedars of the Lord

The cedars of Lebanon, embodying the country’s biological and cultural legacy, are cited more than seventy times in the Bible. Cedar resin was used by Egyptians to preserve mummies, and this might be another reason why the valley is called Qadisha.

Oh, and pots are put on the rocks of the Qadisha Valley if couples become fertile. This practice may also date back to Phoenician times, apparently.

There are at least two significant monasteries in the Qadisha Valley. I visited the Monastery of St Anthony the Great at Qozhaya, a locality whose name is thought to mean treasure of life, referring to Christ or to the locally abundant greenery, or both. St Anthony the Great was a notable caster-out of demons, who was said to be able to cure the mentally ill. The monastery is next to a cave where people came to be cured of mental illness by treatments that included a ritual of exorcism; it has chains that were used to chain up the most insane individuals until they were cured.

According to my guide, Arabic was so strongly identified with Islam in its early days that the Christian Maronites were required to use the Syriac alphabet — which looks a bit like Arabic to Westerners but not quite the same — for all their writings, even the ones that were actually in Arabic! I wonder whether this was to prevent Christian arguments from being mistaken for Islamic teachings; a form of confusion that could easily have arisen otherwise.

The practice was known as Garshuni, which to modern-day linguists has a more general significance meaning writing one language in the writing system of another.

The final place I went to in the Qadisha Valley was the Kahlil Gibran museum, after the famous poet-philosopher. Born in Bsharri in 1883, Gibran moved with his Maronite family to Boston in the United States while he was still a boy. As so often happened with immigrants to America in this days, his actual forename, more properly rendered in English as Khalil, was mis-spelt Kahlil by an official; and Gibran never did anything about the mis-spelling because it was easier for Americans anyway.

A gifted painter who studied in Paris under Renoir (yes, that Renoir), Gibran is most famous however for his books of poetry and wisdom, The Prophet and Broken Wings.

Published in 1923, The Prophet caught the imagination of a New Age movement that was just taking off in the early 1920s. Its success made Gibran a rich man and the world’s third most widely-read poet after Shakespeare and the Chinese sage Lao Tzu.

However, the critics thought that, in spite of a few good lines, it was mostly pretty syrupy stuff; a whole lot of noble sentiments that hardly anybody could disagree with. Most New Age literature is like that of course. Gibran, who yearned to be taken seriously as an artist, was so disappointed that he died of the effects of a mixture of drink and tuberculosis in 1931, at the age of only 48.

His body was taken back to the Qadisha Valley and interred in an annex of the newly-established museum, a former monastery that his sister purchased from the monks. The museum leads into a cave-complex, a sort of sacred grotto, and is not far from where the Phoenician kings are buried in the same grotto. Was this a none-too-subtle message from the sister to the critics, I wonder?

Though he wasn’t especially political, Gibran did espouse a cause known as Syrian nationalism. The Syria in question wasn’t modern Syria but rather a sort of United States of the Levant, a highly progressive country that would have unified the several famous and historic cities of the Levant from Antioch, Alexandretta and Damascus in the north down to Jerusalem, Gaza and Amman in the south, by way of Beirut, Haifa and Jaffa (now Tel Aviv/Yafo). This was also part of the vision of Col. T. E. Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

A short-lived Arab Kingdom of Syria was provisionally established across the whole of the Levant under Emir Faisal of the Hashemite dynasty, a companion of T. E. Lawrence from the days of their romantic freedom-fight against the Ottomans. But the Hashemites, desert warriors from what is now Saudi Arabia, did not have any political or tribal roots along the Mediterranean shore.

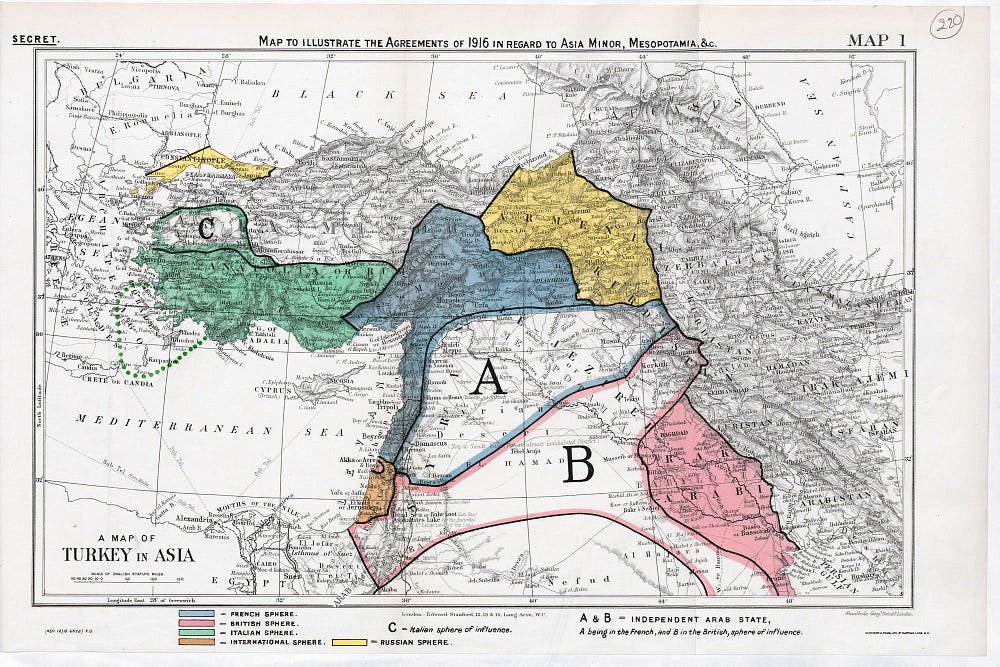

The shallow-rooted kingdom was soon blown over by the colonial powers, who had their own plans for the carve-up of the former Ottoman realm, the infamous Sykes-Picot agreement that split the Levant between French and British spheres of influence while at the same time handing Iraq to Britain, Istanbul and eastern Turkey to the Russians, and the southwestern part, including Cappadocia, to Italy. The Kemalist Turks managed to re-unite the part that became modern Turkey, but the Levantine provinces and Iraq were colonised more-or-less as planned.

After the carve-up of the Levant, the Hashemites, who also populated some other short-lived Middle Eastern monarchies including a British-dominated Iraq, would manage to cling on, more successfully but less ambitiously, as rulers of another British protectorate called the Emirate of Transjordan; which in time evolved into the present Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, or Jordan as it is known for short.

Perhaps if it had been more firmly and legitimately established, a commonwealth of all the Levant could have absorbed a large Jewish population after World War II without coming apart at the seams. With this infusion, the undoubted prosperity, energy and progress of today’s Israel might have extended from Alexandretta to Gaza and included everyone.

Beaufort Castle really would have been nothing more than a tourist attraction in Gibran’s parallel historical universe.

The failure of Gibran’s vision — of an internationally borderless string of lights along the coast from Alexandretta to Gaza and inland to Damascus, Jerusalem and Amman — also helps to explain why he died a disappointed man. He ended a poem called ‘Pity the Nation’ with the line: “Pity the nation divided into fragments, each fragment deeming itself a nation.”

But who knows. If there is to be a solution to the Middle East conundrum, I feel sure that it will have to include some such realisation of a Levantine commonwealth whether the existing borders remain in place or not.

I mean, look at all those old forts that march from Belgium to Switzerland along the Franco-German border. They’re still there, along with the border. But a certain enlargement of consciousness has made them redundant. As a New Ager, Gibran would certainly have approved of that.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!